The Allure of "More"

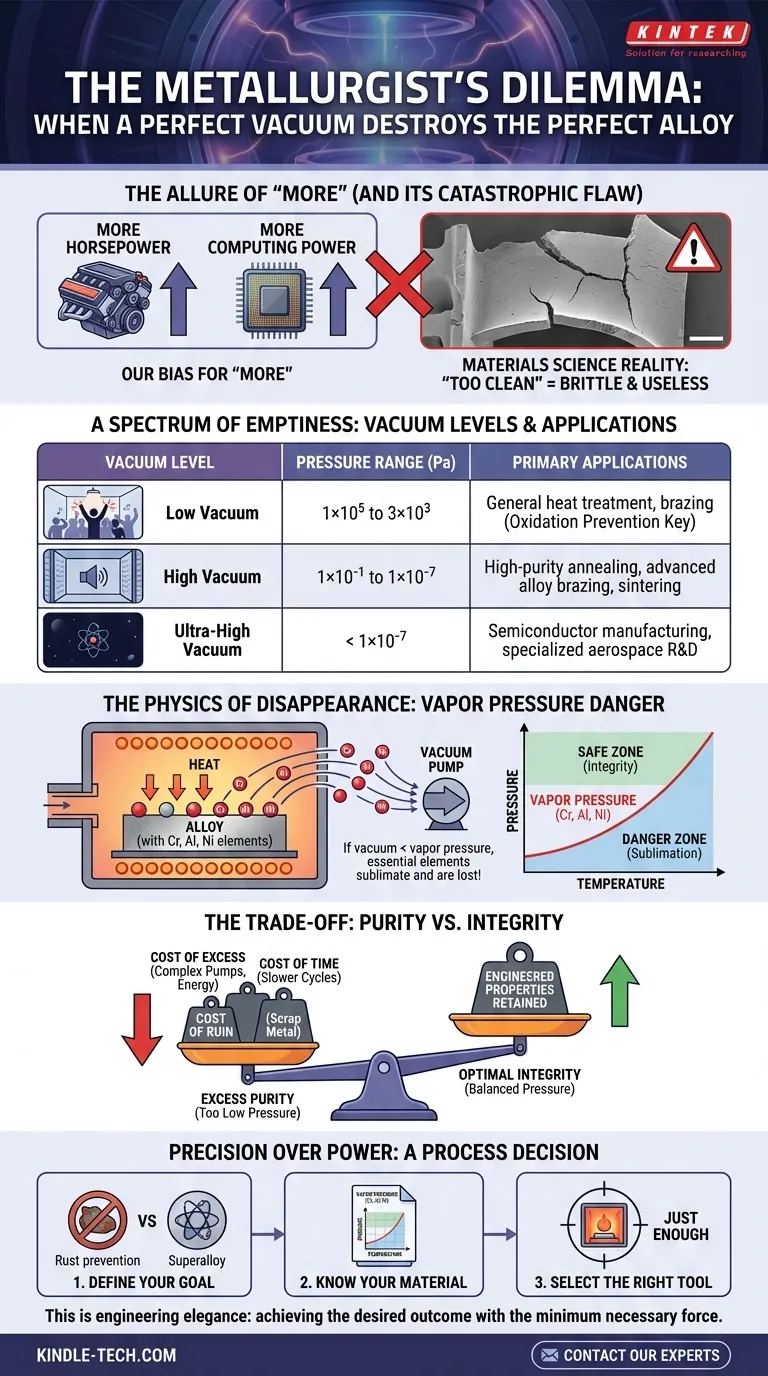

We have a deep-seated bias for "more." We want more horsepower, more megapixels, more computing power. This instinct often serves us well, but in the world of materials science, it can be a catastrophic flaw.

Imagine a metallurgist inspecting a newly heat-treated turbine blade. The part is worth tens of thousands of dollars, forged from a complex superalloy. Yet, under the microscope, its properties are all wrong. The surface is depleted of a critical element, rendering it brittle and useless. The cause? Not contamination, but an environment that was too clean, a vacuum that was too perfect.

This is the central paradox of vacuum thermal processing: the pursuit of absolute purity can sometimes be the very thing that destroys your material.

A Spectrum of Emptiness

A vacuum furnace is defined by the level of emptiness it can achieve. We classify them not as good or bad, but as different tools for different jobs, measured in Pascals (Pa).

- Low Vacuum: Think of this as clearing the room of a loud crowd. It removes the most reactive gases, like oxygen, preventing heavy oxidation. It's perfect for general-purpose jobs.

- High Vacuum: This is like soundproofing the room. It removes the vast majority of molecules, creating a pristine environment for sensitive materials like titanium or advanced alloys used in aerospace and medical implants.

- Ultra-High Vacuum: This is the closest we can get to the void of space. It's for highly specialized applications, like semiconductor research, where even a few stray atoms can ruin the entire process.

The mistake is assuming the ultra-high vacuum tool is inherently the "best" for every task. It’s like using atomic tweezers to assemble a wooden chair.

| Vacuum Level | Pressure Range (Pa) | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Low Vacuum | 1×10⁵ to 3×10³ | General heat treatment, brazing where oxidation prevention is key |

| High Vacuum | 1×10⁻¹ to 1×10⁻⁷ | High-purity annealing, vacuum brazing of advanced alloys, sintering |

| Ultra-High Vacuum | < 1×10⁻⁷ | Semiconductor manufacturing, specialized aerospace R&D |

The Physics of Disappearance

Every element has a secret desire to become a gas. This tendency is called vapor pressure. As you heat a material in a furnace, the vapor pressure of its constituent elements rises dramatically.

Herein lies the danger.

If the pressure inside the furnace—the vacuum level—drops below the vapor pressure of an element in your alloy, that element will begin to sublimate. It literally boils off the surface and is whisked away by the vacuum pumps.

This isn't a minor impurity being removed. This is a fundamental ingredient of your recipe—like chromium, aluminum, or nickel—vanishing into the void. The chemical composition of your alloy is irrevocably altered, and its engineered properties are lost forever.

The Trade-Off: Purity vs. Integrity

The engineer's true task is not to achieve the highest vacuum possible, but to find the perfect equilibrium. The vacuum must be low enough to prevent atmospheric gases from contaminating the workpiece, but high enough to keep the material's own essential elements from escaping.

Choosing wrong has tangible costs:

- The Cost of Excess: High and ultra-high vacuum systems require more sophisticated pumps, consume more energy, and demand more complex maintenance. You pay a premium for a capability you may not need—and which might even be harmful.

- The Cost of Time: Pumping down to a lower pressure takes significantly more time. This extends cycle times, reduces throughput, and increases operational costs.

- The Cost of Ruin: The most significant cost is material loss. An incorrectly specified vacuum can turn a high-performance component into scrap metal, wasting not just materials but invaluable R&D and production time.

Precision Over Power

The choice of a vacuum furnace isn't a procurement decision; it's a critical process engineering decision. It requires a disciplined approach, not a default to "the best."

- Define Your Goal: Are you simply preventing rust on a simple steel part, or are you brazing a complex nickel superalloy where every atom counts?

- Know Your Material: Consult the vapor pressure charts for your specific alloy at your target processing temperature. This data will tell you the pressure "floor" below which you cannot safely operate.

- Select the Right Tool: Choose a furnace that can reliably maintain the precise vacuum window your process requires—no more, no less.

This is the essence of engineering elegance: achieving the desired outcome with the minimum necessary force and complexity. It’s about understanding the system so deeply that you know exactly how much is "just enough."

Navigating the complexities of vapor pressure and process parameters is where expertise becomes invaluable. At KINTEK, we specialize in equipping laboratories with precisely the right tools for their specific challenges. If you're facing the critical choice of a vacuum furnace, don't leave your material's integrity to guesswork. Contact Our Experts

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace and Levitation Induction Melting Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Molybdenum Wire Sintering Furnace for Vacuum Sintering

- Vertical Laboratory Tube Furnace

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

Related Articles

- Vacuum Melting Furnace: A Comprehensive Guide to Vacuum Induction Melting

- Vacuum Induction Melting Furnace: Principle, Advantages, and Applications

- Melting process and maintenance of vacuum induction melting furnace

- Exploring Tungsten Vacuum Furnaces: Operation, Applications, and Advantages

- The Furnace Dilemma: Choosing Between Precision and Scale in Thermal Processing