In manufacturing, as in life, we are often tempted by the path of least resistance. We want a finished product in a single step, a perfect shape straight from the mold.

This desire for immediate precision can be a trap. It leads us to overlook the subtle, invisible flaws that form under pressure—flaws that only reveal themselves later, catastrophically.

Imagine a high-performance ceramic turbine blade, fresh from the sintering furnace. It looks flawless. But under stress, a hairline crack appears, born from a hidden inconsistency deep within the material. The failure didn't happen in the furnace; it was sealed into the part from the very first press.

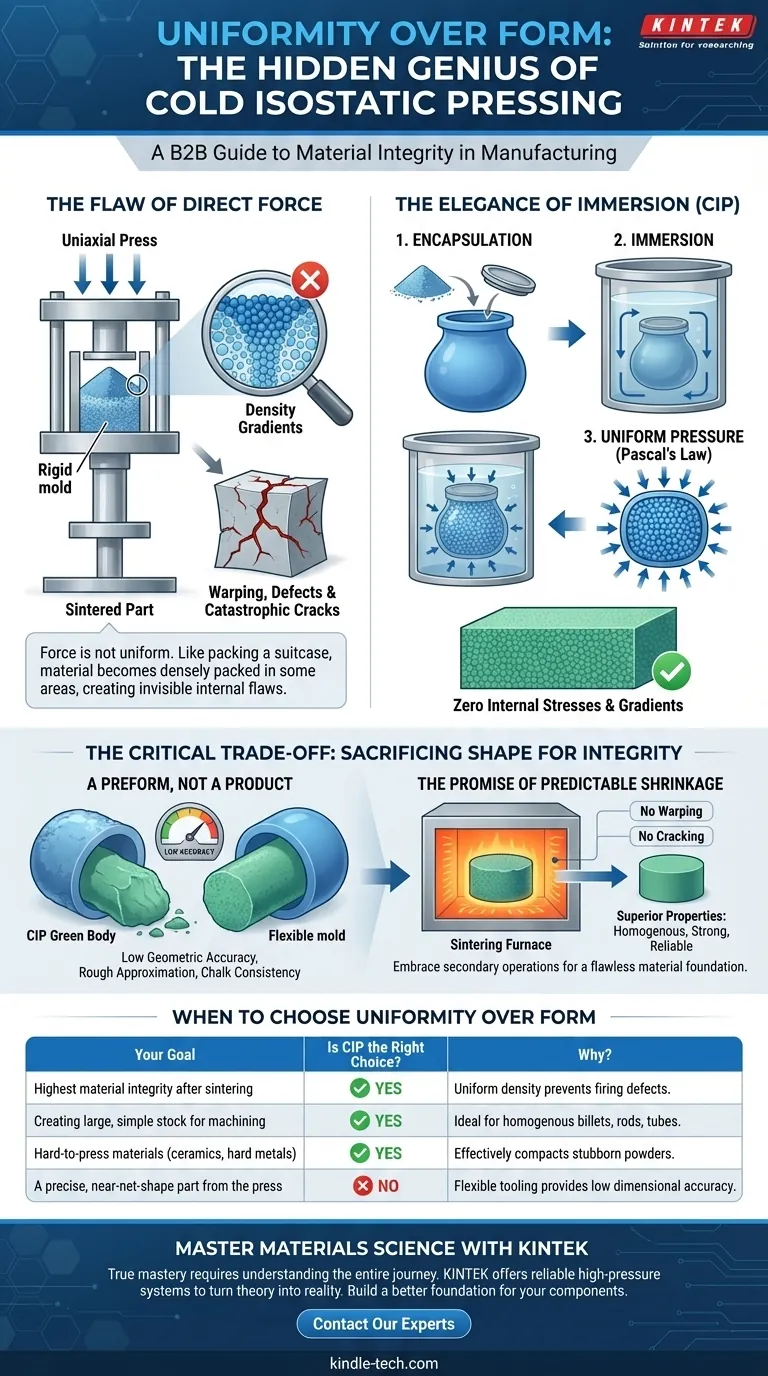

The Flaw of Direct Force

Most conventional pressing methods, like uniaxial pressing, are intuitive. You apply immense force from one or two directions to compact a powder into a desired shape.

The problem is that force is not uniform. Like packing a suitcase by pushing down on the top, the material directly under the press becomes densely packed, while the material in the corners and at the bottom remains looser.

This creates density gradients—invisible internal boundaries between high- and low-density regions. When this "green body" is fired, these regions shrink at different rates. The resulting stress is what causes warping, defects, and the catastrophic cracks that plague high-performance components.

The Elegance of Immersion

Cold Isostatic Pressing (CIP) offers a profoundly different, more elegant philosophy. Instead of applying force directly, it surrounds the material with it.

The process is a beautiful application of a fundamental principle of physics.

- Encapsulation: The raw powder is first sealed in a flexible, elastomeric mold. This mold acts as a barrier, not a rigid boundary.

- Immersion: The sealed mold is submerged in a fluid inside a high-pressure vessel.

- Uniform Pressure: The fluid is then pressurized, sometimes to extreme levels over 100,000 psi. Crucially, a fluid transmits pressure equally in all directions—a principle known as Pascal's Law.

The pressure squeezes the mold from every conceivable angle at the exact same time with the exact same force. The powder particles inside have no choice but to rearrange themselves into a state of remarkably uniform density.

The result is a "green body" free of the internal stresses and gradients created by directional force. It is a perfect foundation.

The Critical Trade-Off: Sacrificing Shape for Integrity

Here we arrive at the central paradox of CIP. The very thing that makes it so effective—the flexible mold—is also its primary limitation.

A Preform, Not a Product

Because the mold deforms, CIP cannot produce parts with high geometric accuracy or fine details. A part emerging from a CIP vessel is not a finished component; it is a preform. It has the consistency of chalk and a shape that is a rough approximation of the final design.

Many engineers, focused on near-net-shape manufacturing, might see this as a fatal flaw. But they are missing the point.

CIP intentionally trades immediate dimensional precision for ultimate material integrity.

The Promise of Predictable Shrinkage

The true value of a CIP-formed green body is revealed in the furnace. Because its density is uniform throughout, it shrinks predictably and evenly during sintering.

- No Warping: Uniform shrinkage prevents the twisting and distortion common in uniaxially pressed parts.

- No Cracking: The absence of internal density gradients eliminates the stress points that lead to cracking.

- Superior Properties: The final sintered part is homogenous, strong, and reliable.

The process embraces the necessity of secondary operations. It accepts that the "blurry" preform will require final machining to meet tight tolerances. But it guarantees that the material being machined is as close to perfect as possible.

When to Choose Uniformity Over Form

The decision to use CIP is a strategic one, based on your ultimate priority.

| Your Goal | Is CIP the Right Choice? | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Highest material integrity after sintering | Yes | Uniform density is the #1 factor in preventing firing defects. |

| Creating large, simple stock for machining | Yes | Ideal for producing homogenous billets, rods, or tubes. |

| Hard-to-press materials (ceramics, hard metals) | Yes | The isostatic pressure effectively compacts stubborn powders. |

| A precise, near-net-shape part from the press | No | The flexible tooling inherently provides low dimensional accuracy. |

True mastery of materials science lies in understanding the entire journey of a component, from loose powder to finished part. By focusing on creating a flawless foundation, Cold Isostatic Pressing enables a level of quality that direct-shaping methods simply cannot match.

Achieving this level of material integrity requires not just the right philosophy, but the right equipment. For laboratories working on the frontier of materials science, having reliable high-pressure systems like those from KINTEK is critical to turning theory into reality. If you're ready to build a better foundation for your components, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Electric Split Lab Cold Isostatic Press CIP Machine for Cold Isostatic Pressing

- Electric Lab Cold Isostatic Press CIP Machine for Cold Isostatic Pressing

- Manual Cold Isostatic Pressing Machine CIP Pellet Press

- Automatic Lab Cold Isostatic Press CIP Machine Cold Isostatic Pressing

- Manual High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

Related Articles

- Cold Isostatic Pressing: An Overview and its Industrial Applications

- How Isostatic Presses Improve the Efficiency of Material Processing

- Understanding Cold Isostatic Pressing and its Types

- Hot & Cold Isostatic Pressing: Applications, Process, and Specifications

- Cold Isostatic Pressing (CIP): A Proven Process for High-Performance Parts Manufacturing