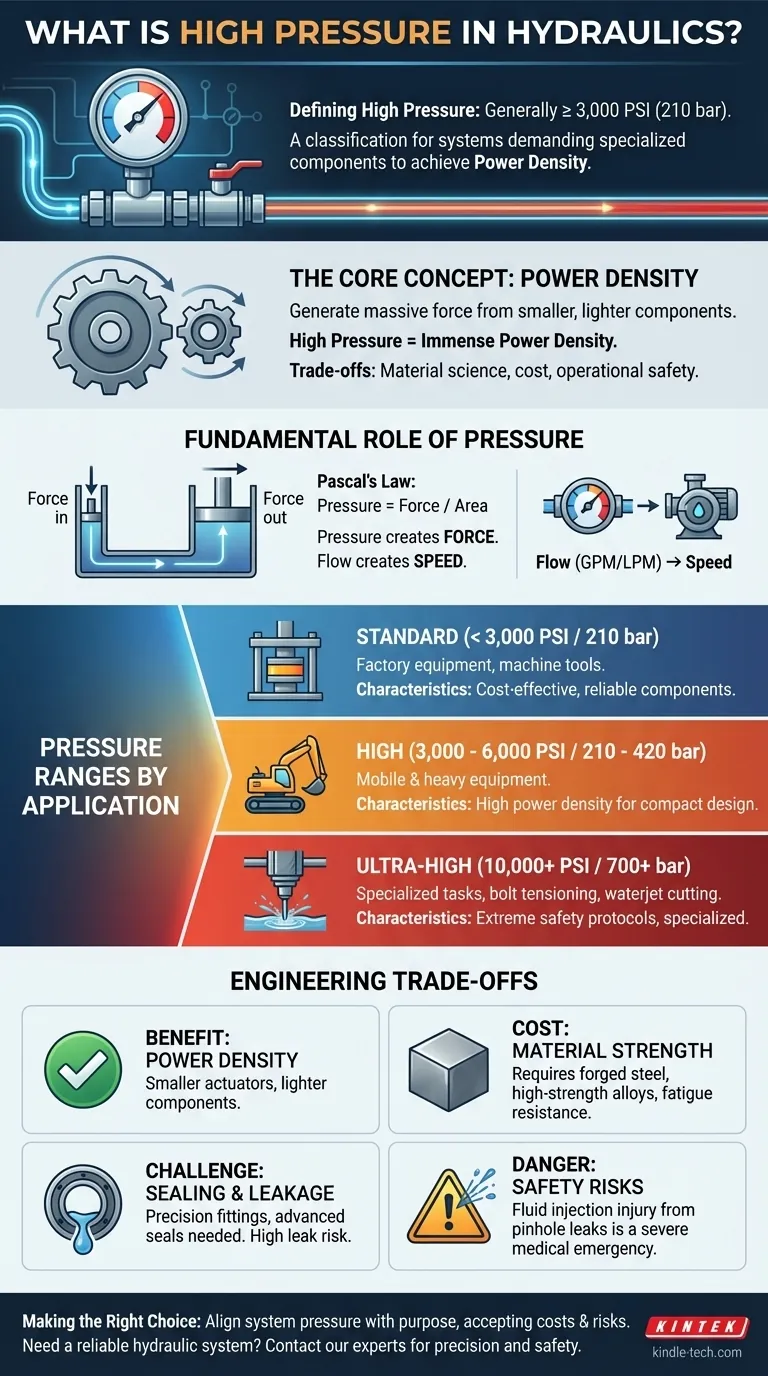

In hydraulics, "high pressure" is not a single, universally defined number, but rather a classification for systems operating at pressures that demand specialized components and design considerations. Generally, this range begins around 3,000 PSI (210 bar) and can extend beyond 10,000 PSI (700 bar) for specialized ultra-high pressure applications.

The core concept to grasp is that high pressure is a tool for achieving immense power density—generating massive force from smaller, lighter components. This benefit, however, comes with significant trade-offs in material science, component cost, and operational safety.

The Fundamental Role of Pressure in Hydraulics

To understand what makes "high pressure" significant, we must first revisit the core principle of how any hydraulic system functions. It's all about transmitting force through an incompressible fluid.

Pressure vs. Force: The Core Principle

The foundation of all hydraulics is Pascal's Law, which states that pressure applied to a confined fluid is transmitted undiminished in all directions.

The relationship is simple: Pressure = Force / Area. This means you can generate a massive output force with a relatively small input force simply by changing the surface area (e.g., the size of a hydraulic cylinder's piston).

How Pressure Enables Work

Pressure is the "potential" in the system. A hydraulic pump creates flow, but when that flow meets resistance (like a heavy load on a cylinder), pressure builds.

It is this pressure, acting on the surface area of a piston or motor, that generates the force needed to lift a car, crush rock, or bend steel. Higher pressure means more force can be generated for a given component size.

The Relationship with Flow

A common point of confusion is the relationship between pressure and speed. Pressure creates force, while flow (measured in GPM or LPM) creates speed.

A system can have extremely high pressure but move very slowly if the flow rate is low. Conversely, a low-pressure system can move very quickly with a high flow rate. The two are independent variables that together determine the system's power output.

Defining "High Pressure" by Application

Because the term is relative, it's more useful to define pressure ranges by their common industrial and mobile applications.

Standard Industrial Systems (Up to 3,000 PSI / 210 bar)

This is the workhorse range for a vast number of applications. You will find these pressures in factory equipment like hydraulic presses, machine tools, injection molding machines, and stationary material handlers. Components are widely available and relatively economical.

Mobile and Heavy Equipment (3,000 - 6,000 PSI / 210 - 420 bar)

This is the most common range referred to as "high pressure." It is standard in mobile machinery like excavators, bulldozers, and cranes. The primary driver for using these pressures is power density—getting the maximum force from compact components that can fit on a vehicle.

Specialized and Ultra-High Pressure (UHP) Systems (10,000+ PSI)

This realm is for highly specialized tasks. Systems operating at 10,000 PSI (700 bar) are used for hydraulic bolt tensioning and portable lifting jacks.

Ultra-high pressure (UHP) systems, which can exceed 40,000 PSI, are used for applications like waterjet cutting and hydrostatic testing, where the goal is to use a pressurized fluid stream to perform work itself.

Understanding the Engineering Trade-offs

Choosing to design or operate a high-pressure system is an engineering decision with clear benefits and significant drawbacks.

The Benefit: Power Density

This is the primary reason to use high pressure. By doubling the system pressure, you can get the same amount of force from an actuator with half the surface area. This leads to smaller, lighter, and often more responsive components, which is critical for mobile equipment.

The Cost: Material Strength and Fatigue

Containing high pressure requires robust materials. Components for high-pressure systems are typically made from forged steel or high-strength alloys, rather than less expensive cast iron or aluminum. They must be engineered not just to withstand the peak pressure but to resist the metal fatigue caused by millions of pressure cycles.

The Challenge: Sealing and Leakage

As pressure increases, the fluid has a much greater tendency to find an escape path. High-pressure systems demand precision-machined fittings, specialized O-rings, and advanced seal materials to prevent leaks. Even a minor leak can quickly drain a system and create a significant mess.

The Danger: Safety Risks

This is the most critical trade-off. A pinhole leak in a high-pressure hydraulic line can release a stream of fluid at near-supersonic speed. If this stream contacts skin, it can cause a fluid injection injury, which is a severe medical emergency that can lead to amputation or death. The high pressure injects toxic hydraulic fluid deep into tissues, requiring immediate surgical intervention.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Selecting a pressure range is about aligning the system's capabilities with its intended purpose and accepting the associated costs and risks.

- If your primary focus is reliability and cost-effectiveness for stationary tasks: A standard pressure system (below 3,000 PSI) is almost always the superior choice.

- If your primary focus is compact power for mobile equipment: High pressure (3,000 - 6,000 PSI) is the industry standard and a necessary trade-off for achieving performance goals.

- If your primary focus is extreme force from a portable tool or specialized cutting: Ultra-high pressure (10,000+ PSI) systems are required, demanding expert design and uncompromising safety protocols.

Ultimately, understanding the role of pressure empowers you to specify, operate, and maintain hydraulic systems that are not only powerful but also efficient and safe.

Summary Table:

| Pressure Range | Typical Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Standard (Up to 3,000 PSI) | Factory presses, machine tools | Cost-effective, reliable components |

| High (3,000 - 6,000 PSI) | Excavators, bulldozers, cranes | High power density for mobile equipment |

| Ultra-High (10,000+ PSI) | Waterjet cutting, bolt tensioning | Specialized components, extreme safety protocols |

Need a reliable hydraulic system for your lab or industrial application? KINTEK specializes in high-performance lab equipment and hydraulic components designed for precision and safety. Whether you require standard pressure reliability or specialized high-pressure solutions, our expertise ensures you get the right balance of power, efficiency, and durability. Contact our experts today to discuss your specific hydraulic needs!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Manual High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

- Customizable High Pressure Reactors for Advanced Scientific and Industrial Applications

- Mini SS High Pressure Autoclave Reactor for Laboratory Use

- Automatic High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

- Stainless High Pressure Autoclave Reactor Laboratory Pressure Reactor

People Also Ask

- Why are hydraulic presses dangerous to operate? Uncover the Silent, Deceptive Risks

- How much force can a hydraulic press exert? Understanding its immense power and design limits.

- What does a hydraulic heat press do? Achieve Industrial-Scale, Consistent Pressure for High-Volume Production

- How does a vacuum furnace environment influence sintered Ruthenium powder? Achieve High Purity and Theoretical Density

- What causes hydraulic pressure spikes? Prevent System Damage from Hydraulic Shock