The application of ultra-high pressure is the decisive factor in overcoming the high resistance typically found at solid-solid interfaces. By exerting forces as high as 360 MPa, laboratory hydraulic presses utilize the inherent ductility of lithium metal to physically deform the anode, forcing it into atomic-level contact with the hard solid-state electrolyte layer.

Core Takeaway: The ultra-high pressure step does not merely push components together; it mechanically "flows" the soft lithium metal onto the hard electrolyte surface. This eliminates microscopic voids to drastically reduce impedance, enabling the battery to function stably during high-rate charging and discharging.

The Mechanics of Atomic-Level Attachment

Exploiting Material Properties

The effectiveness of this process relies on the physical difference between the two mating materials.

Lithium metal is naturally ductile (soft and malleable), whereas the solid-state electrolyte layer is hard.

Transforming the Interface

When 360 MPa of pressure is applied, the lithium anode behaves almost like a fluid.

It deforms to fill the microscopic irregularities on the surface of the hard electrolyte.

This creates a tight, atomic-level contact that is impossible to achieve through simple placement or low-pressure assembly.

Impact on Battery Performance

Minimizing Interface Impedance

The primary obstacle in solid-state batteries is the resistance to ion flow between layers.

By eliminating physical gaps and voids via ultra-high pressure, you minimize the interface impedance on the lithium anode side.

This ensures that lithium ions can traverse the boundary between the anode and electrolyte without significant energy loss.

Ensuring Stability at High Rates

A poor interface leads to hotspots, uneven plating, and rapid degradation during operation.

The tight contact achieved through this pressurization ensures the battery remains stable even during high-rate charge and discharge cycles.

This mechanical bonding is essential for the battery to deliver high power outputs reliably.

Understanding the Distinctions and Trade-offs

Fabrication Pressure vs. Operating Pressure

It is critical to distinguish between the pressure used for attachment and the pressure used for cycling.

The ultra-high pressure (360 MPa) described here is a fabrication step intended to create the initial bond using the anode's ductility.

This is distinct from the continuous, often lower, external pressure required during battery cycling to counteract the volume expansion of sulfur cathodes mentioned in supplementary contexts.

The Necessity of Extreme Force

Using lower pressures during the anode attachment phase is a common pitfall.

Insufficient pressure fails to deform the lithium enough to establish atomic contact, leaving voids that result in high resistance.

You cannot rely on the "stickiness" of lithium alone; mechanical deformation via ultra-high pressure is a requirement for high-performance cells.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

To optimize your solid-state battery assembly, align your pressure strategy with your specific performance objectives:

- If your primary focus is High-Rate Performance: Prioritize the 360 MPa ultra-high pressure step during anode attachment to minimize impedance and ensure rapid ion transport.

- If your primary focus is Cycle Life: Ensure that after the initial ultra-high pressure bonding, you also implement a continuous external pressure system to manage volume expansion during operation.

Success in all-solid-state lithium-sulfur batteries begins with forcing the soft anode and hard electrolyte into a unified, void-free interface.

Summary Table:

| Feature | Mechanism | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure Level | 360 MPa (Ultra-High) | Forces lithium to 'flow' into electrolyte irregularities |

| Interface Type | Solid-to-Solid | Eliminates microscopic voids and air gaps |

| Material Synergy | Ductile Li + Hard Electrolyte | Creates atomic-level contact via mechanical deformation |

| Ion Transport | Minimized Impedance | Enables stable high-rate charging and discharging |

Optimize Your Battery Research with KINTEK Precision

High-performance all-solid-state lithium-sulfur batteries demand absolute precision and extreme force. KINTEK specializes in providing the specialized laboratory equipment needed to bridge the gap between material science and functional energy storage.

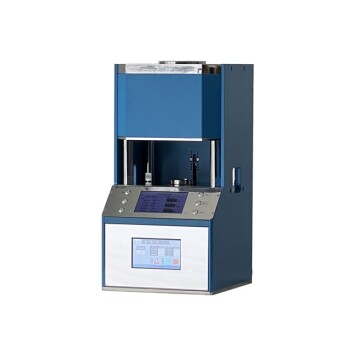

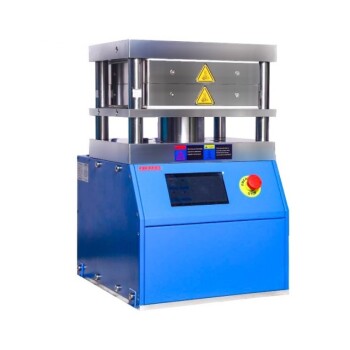

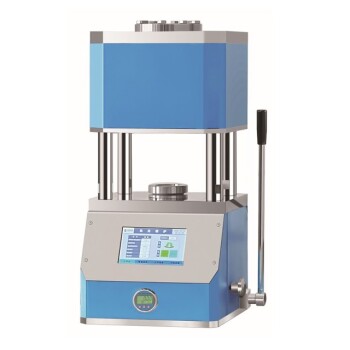

Our professional-grade laboratory hydraulic presses (pellet, hot, and isostatic) are designed to deliver the consistent, ultra-high pressure required for atomic-level anode attachment. Beyond pressing, KINTEK offers a comprehensive ecosystem for battery innovation, including:

- Battery research tools and consumables for precise cell assembly.

- High-temperature furnaces (vacuum, CVD, atmosphere) for electrolyte synthesis.

- Crushing, milling, and sieving systems for material preparation.

- Electrolytic cells and electrodes for advanced electrochemical testing.

Don't let interface resistance stall your research. Partner with KINTEK to access the reliable tools and technical expertise your laboratory needs. Contact us today to find the perfect hydraulic press for your battery assembly workflow!

Related Products

- Automatic High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

- Manual High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Laboratory Hot Press 25T 30T 50T

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Split Electric Lab Pellet Press

- Automatic Laboratory Hydraulic Press for XRF & KBR Pellet Press

People Also Ask

- What is a hot hydraulic press? Harness Heat and Pressure for Advanced Manufacturing

- How much force can a hydraulic press exert? Understanding its immense power and design limits.

- How does a heated laboratory hydraulic press facilitate densification in CSP? Optimize Mg-doped NASICON Sintering

- What are heated hydraulic presses used for? Molding Composites, Vulcanizing Rubber, and More

- How does a vacuum furnace environment influence sintered Ruthenium powder? Achieve High Purity and Theoretical Density