Buying laboratory equipment is rarely just a financial transaction. It is an operational bet on the quality of your future data.

When selecting a tube furnace, there is a temptation to shop for the "best" model—the one with the highest maximum temperature or the most complex control system. This is a mistake.

In the laboratory, "best" is a meaningless metric. "Aligned" is what matters.

A furnace is not a standalone artifact; it is a component in a larger system of synthesis, heat treatment, or testing. To choose the right one, you must ignore the marketing brochures for a moment and look strictly at the non-negotiable physics of your specific application.

Here is how to deconstruct the decision.

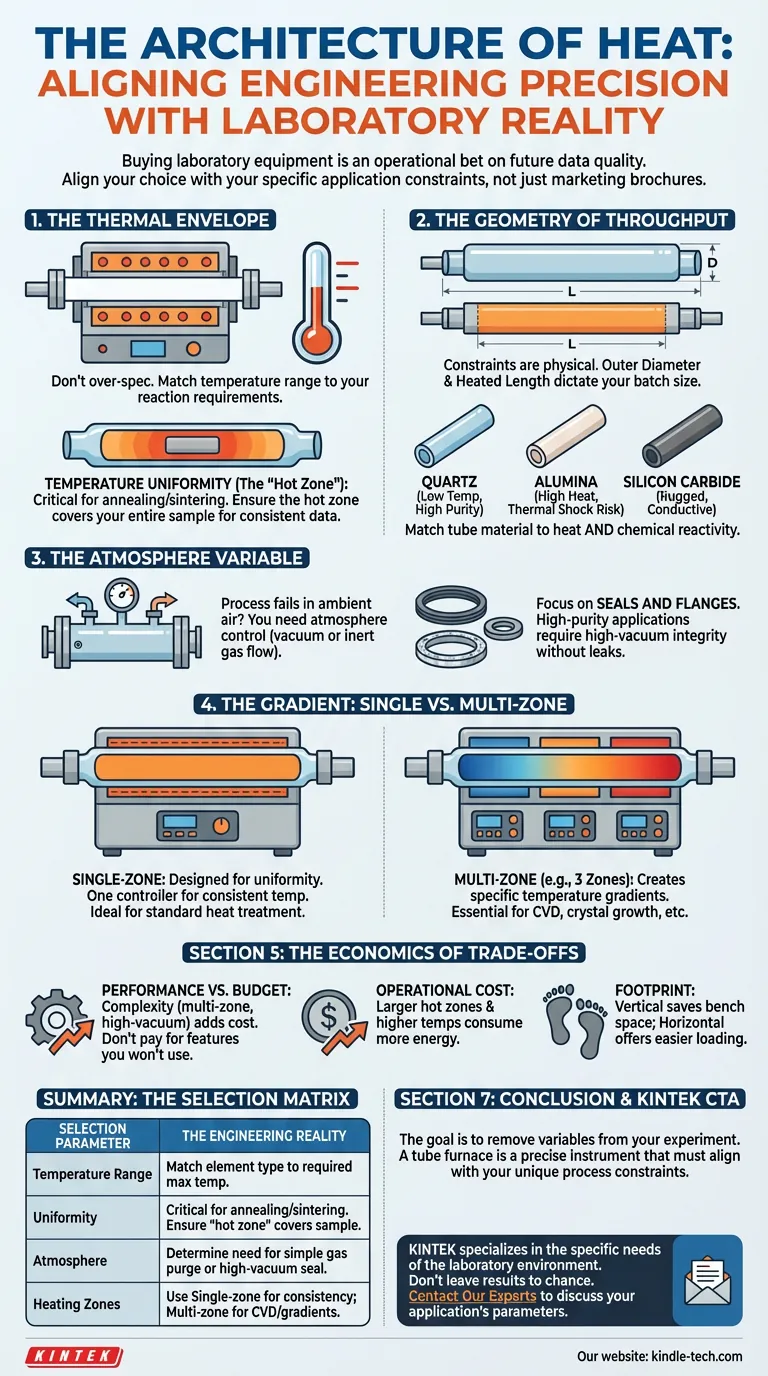

1. The Thermal Envelope

The most obvious specification is often the most misunderstood. You know the temperature your reaction requires. But a furnace rated for 1700°C is vastly different—and significantly more expensive—than one rated for 1200°C.

The engineering challenge here isn't just hitting a number; it is repeatability.

Temperature Uniformity is the silent partner of successful experimentation. In annealing or sintering, a variation of even a few degrees across the tube can alter the crystalline structure of your sample. You aren't paying for heat; you are paying for consistency.

Ensure the heating elements are capable of maintaining a uniform "hot zone" that covers the entire length of your sample.

2. The Geometry of Throughput

In systems engineering, constraints are usually physical. In a tube furnace, the constraint is the tube itself.

The Outer Diameter and Heated Length dictate your throughput. A larger diameter allows for larger batches, but it changes the thermal dynamics.

Furthermore, the material of the tube is a critical interface.

- Quartz: Excellent for lower temperatures and high purity.

- Alumina: Essential for high heat but susceptible to thermal shock.

- Silicon Carbide: Rugged and conductive.

You must match the tube material not just to the heat, but to the chemical reactivity of your samples.

3. The Atmosphere Variable

Many modern materials science processes fail in ambient air. Oxygen is often the enemy.

If your process requires oxidation-sensitive handling, the furnace becomes a vessel for atmosphere control. You are no longer just managing heat; you are managing a vacuum or a flow of inert gas.

This requires a shift in focus to the seals and flanges. A furnace intended for high-purity applications must be capable of sustaining a high vacuum without leak rates that compromise the sample integrity.

4. The Gradient: Single vs. Multi-Zone

This is where the application strictly dictates the hardware.

Single-Zone Furnaces are designed for uniformity. They have one controller and one goal: keep the entire tube at $X$ degrees. This is the workhorse for standard heat treatment.

Multi-Zone Furnaces (typically three zones) are instruments of nuance. With independent controllers, you can create a specific temperature gradient across the tube.

If you are doing Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) or crystal growth, a single-zone furnace is useless. You need the ability to manipulate thermal profiles to drive deposition at specific rates.

The Economics of Trade-offs

Every engineering decision involves a trade-off. In furnace selection, the trade-off is usually between flexibility and efficiency.

- Performance vs. Budget: High-vacuum compatibility and multi-zone control add complexity and cost. Do not pay for a temperature gradient you will never use.

- Operational Cost: Larger hot zones and higher temperatures consume exponentially more energy.

- Footprint: Vertical furnaces save bench space; horizontal furnaces offer easier loading.

Summary: The Selection Matrix

To simplify the decision, map your needs against this framework:

| Selection Parameter | The Engineering Reality |

|---|---|

| Temperature Range | Don't over-spec. Match the element type to your required max temp. |

| Uniformity | Critical for annealing/sintering. Ensuring the "hot zone" covers the sample. |

| Atmosphere | Determine if you need a simple gas purge or a high-vacuum seal. |

| Heating Zones | Use Single-zone for consistency; Multi-zone for CVD/gradients. |

Conclusion

The goal is not to buy a machine. The goal is to remove variables from your experiment.

If your furnace is too small, you create a bottleneck. If the temperature fluctuates, you create noise in your data. If the seals leak, you create contamination.

At KINTEK, we specialize in the specific needs of the laboratory environment. We understand that a tube furnace is a precise instrument that must align with your unique process constraints.

Don't leave your results to chance. Contact Our Experts to discuss your application's parameters, and let us help you engineer the perfect thermal solution.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1700℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- 1200℃ Split Tube Furnace with Quartz Tube Laboratory Tubular Furnace

- Laboratory Rapid Thermal Processing (RTP) Quartz Tube Furnace

- Laboratory Vacuum Tilt Rotary Tube Furnace Rotating Tube Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Molybdenum Wire Sintering Furnace for Vacuum Sintering

Related Articles

- The Silent Partner in Pyrolysis: Engineering the Perfect Thermal Boundary

- Why Your Ceramic Furnace Tubes Keep Cracking—And How to Choose the Right One

- Your Tube Furnace Is Not the Problem—Your Choice of It Is

- Entropy and the Alumina Tube: The Art of Precision Maintenance

- Installation of Tube Furnace Fitting Tee