Oxygen is a thief.

In the natural world, air is the medium of life. In the world of high-performance metallurgy, however, air is an aggressive contaminant. It steals electrons. It creates oxide layers. It compromises the structural integrity of the very materials we rely on to hold up bridges or keep airplanes in the sky.

The engineering solution to this problem is radical in its simplicity but complex in its execution: remove the atmosphere entirely.

The vacuum furnace is not merely a tool for getting things hot. It is a controlled environment designed to pause the laws of entropy. By processing materials in a void, we stop nature from doing what it does best—corroding and contaminating—allowing us to achieve a level of purity that is physically impossible in the open air.

Here is the logic behind the silence of the vacuum process.

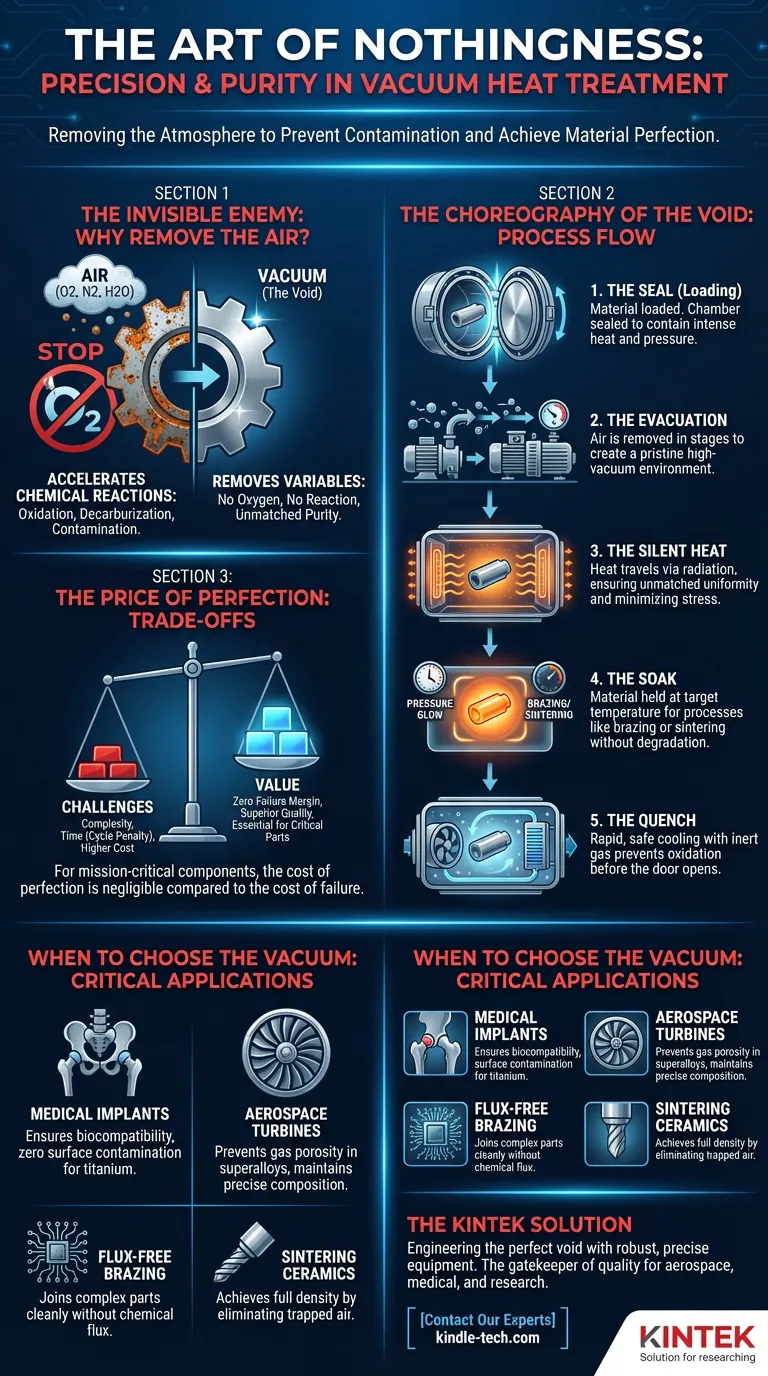

The Invisible Enemy: Why We Remove the Air

To understand the machine, you must understand the failure it prevents.

When you heat steel, titanium, or superalloys in the presence of air, chemical reactions accelerate. Oxygen attacks the surface. Nitrogen reacts with the metal lattice. Water vapor introduces hydrogen embrittlement.

The results are catastrophic for high-precision parts:

- Oxidation: Tarnish and scale that ruin surface finishes.

- Decarburization: The loss of carbon in steel, resulting in a soft, weak surface.

- Contamination: Impurities that weaken the material’s fatigue life.

A vacuum furnace is a fortress. By removing the atmosphere, we remove the variables. There is no oxygen to react. There is no carbon to drift away. There is only the material and the heat.

The Choreography of the Void

The process of a vacuum furnace is slow, deliberate, and unforgiving. It follows a specific rhythm designed to protect the workpiece at every stage.

1. The Seal (Loading)

The process begins with a vessel. The chamber is typically double-walled and water-cooled to contain intense internal heat while keeping the exterior safe. The material is loaded, and the door is sealed.

This seal is the single most critical component. It creates the boundary between the chaos of the atmosphere and the order of the process.

2. The Evacuation

Before heat is applied, the air must go. This is rarely done in a single step.

- Roughing: A mechanical pump removes the bulk of the air, creating a "rough" vacuum.

- High Vacuum: A diffusion or turbomolecular pump takes over, hunting down the remaining molecules to achieve a pristine environment.

3. The Silent Heat

In a conventional oven, heat travels via convection—air moving over the part. In a vacuum, there is no air to move.

Heat must travel via radiation. Whether through graphite resistance elements or induction coils, energy is transferred directly to the workpiece as light energy. This results in unmatched uniformity. The heat soaks through the part evenly, minimizing the internal stresses that cause warping.

4. The Soak

The material sits at the target temperature. This is where the magic happens—brazing alloys flow into capillaries, or crystal structures realign during sintering. Because the environment is inert, this can continue for hours without the risk of surface degradation.

5. The Quench

Cooling is just as dangerous as heating. Opening the door at high temperatures would cause immediate, explosive oxidation.

Instead, the furnace is backfilled with an inert gas—usually Argon or Nitrogen. A powerful fan circulates this gas through a heat exchanger, stripping the heat away from the part rapidly but safely. Only when the temperature is stable does the door open.

The Price of Perfection

If vacuum processing is superior, why isn't it used for everything?

It comes down to the psychology of trade-offs. Perfection is expensive.

- Complexity: Vacuum systems require complex pumps, gauges, and water-cooling systems that demand rigorous maintenance. A single leaking seal ruins the batch.

- Time: Pumping a chamber down to a high vacuum takes time. It adds a "penalty" to the cycle time that atmospheric furnaces don't suffer.

- Cost: The capital investment is significantly higher.

However, for mission-critical components, this cost is negligible compared to the cost of failure.

When to Choose the Vacuum

You do not use a vacuum furnace to bake a brick. You use it when the margin for error is zero.

| Application Goal | Why Vacuum is Essential |

|---|---|

| Medical Implants | Titanium reacts violently with oxygen. Vacuum ensures biocompatibility and zero surface contamination. |

| Aerospace Turbines | Superalloys require precise chemical composition. Vacuum induction melting prevents gas porosity. |

| Flux-Free Brazing | Complex electronics or honeycombs cannot be cleaned of flux. Vacuum brazing joins them cleanly without chemical agents. |

| Sintering Ceramics | To achieve full density in tungsten carbide or ceramics, trapped air must be eliminated completely. |

The KINTEK Solution

There is a romance to engineering a perfect void. It requires a machine that is robust enough to withstand intense pressure differentials yet precise enough to control temperature within a single degree.

At KINTEK, we specialize in the equipment that makes this possible. We understand that for our clients—whether in aerospace, medical manufacturing, or advanced research—the vacuum furnace is not just a heater. It is the gatekeeper of quality.

From high-vacuum pumps to advanced heating elements, we provide the tools necessary to win the battle against oxidation.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Brazing Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Graphite Vacuum Furnace High Thermal Conductivity Film Graphitization Furnace

Related Articles

- More Than Nothing: The Art of Partial Pressure in High-Temperature Furnaces

- The Architecture of Emptiness: Achieving Metallurgical Perfection in a Vacuum

- Your Furnace Hit the Right Temperature. So Why Are Your Parts Failing?

- The Engineering of Nothingness: Why Vacuum Furnaces Define Material Integrity

- Beyond Heat: Mastering Material Purity in the Controlled Void of a Vacuum Furnace