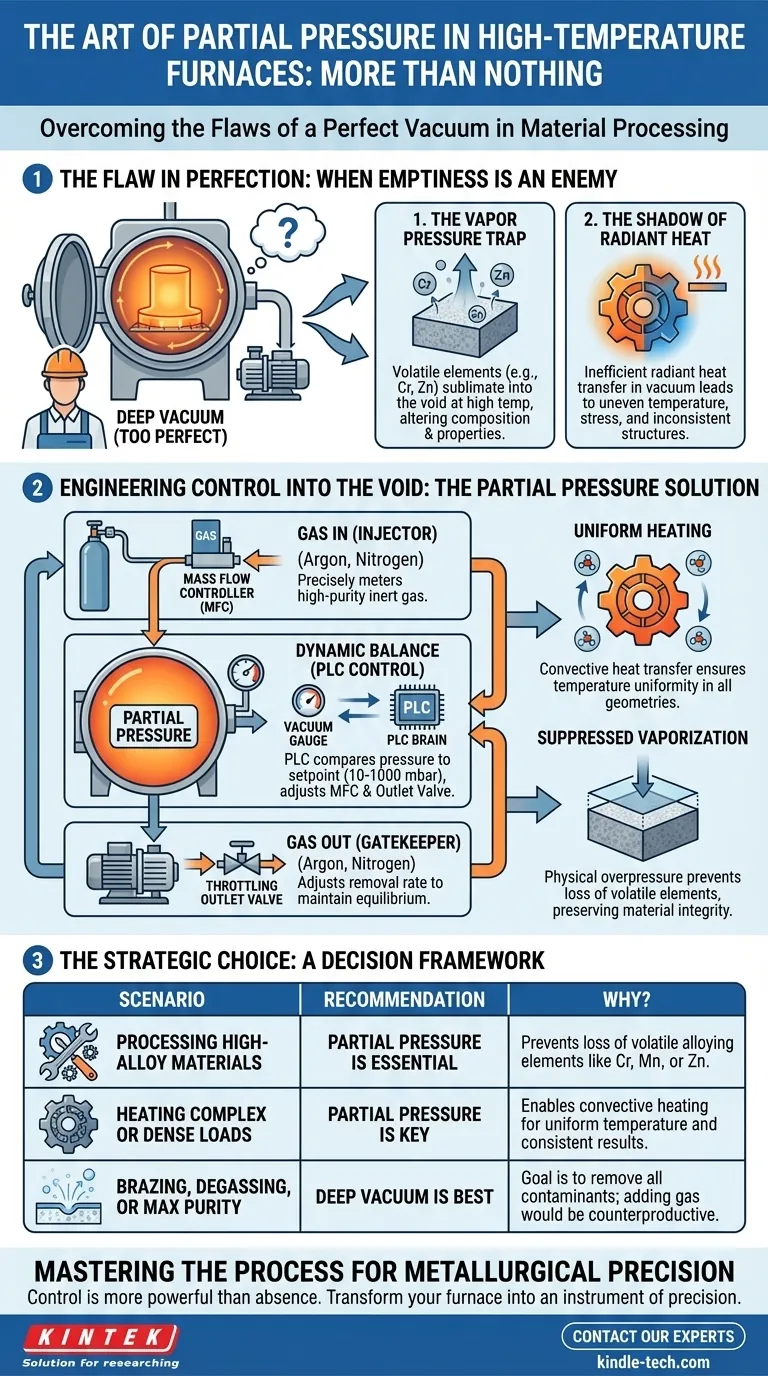

The Flaw in Perfection

Imagine an engineer pulling a newly treated component from a vacuum furnace. It was heated under the purest vacuum possible, shielded from all atmospheric contaminants. Yet, something is wrong. Its surface chemistry is off, its mechanical properties compromised.

The culprit wasn't a failure of the system, but a success. The vacuum was too perfect.

This reveals a common psychological blind spot in engineering: the assumption that more is always better. We think a harder vacuum—a deeper state of nothingness—must yield a cleaner, superior result. But in the world of high-temperature material science, absolute emptiness can be your enemy.

The Physics of Absence

A deep vacuum is an extreme environment. While it excels at preventing oxidation, its very nature creates two subtle but critical problems that can undermine the integrity of your work.

The Vapor Pressure Trap

At high temperatures, a vacuum isn't just empty space; it's an invitation. For certain alloying elements with high vapor pressures—like chromium in tool steel or zinc in brass—the lack of atmospheric pressure on the material's surface allows them to "boil" away, sublimating directly into the void.

This isn't a minor effect. It fundamentally alters the material's composition, stripping it of critical elements and compromising its final properties. The very process designed to protect the material ends up damaging it.

The Shadow of Radiant Heat

In a vacuum, the primary mode of heat transfer is radiation. Heat travels in straight lines from the heating elements to the workpiece. This is incredibly inefficient for parts with complex geometries.

Areas directly exposed to the elements get hot, while crevices, holes, and shadowed sections remain cooler. This uneven temperature distribution leads to inconsistent metallurgical structures, internal stresses, and unpredictable results. The vacuum, an excellent electrical insulator, is also a powerful thermal insulator.

Engineering Control into the Void

The solution to these problems is a masterful paradox: to improve the vacuum process, you must intentionally add gas back into it.

This technique, known as partial pressure control, transforms the furnace from a simple void into a precisely managed, low-density atmosphere. It's not about abandoning the vacuum; it's about refining it.

A Delicate Balance: Gas In, Gas Out

Achieving a stable partial pressure is a dynamic, closed-loop dance managed by a programmable logic controller (PLC).

- The Injector: A Mass Flow Controller (MFC) precisely meters a stream of high-purity inert gas, like argon or nitrogen, into the chamber.

- The Gatekeeper: While gas flows in, the vacuum pumps continue to run. A throttling or outlet valve between the chamber and the pumps adjusts how quickly the gas is removed.

- The Brain: A sensitive vacuum gauge constantly measures the chamber pressure. The PLC reads this data, compares it to the desired setpoint (typically 10 to 1000 mbar), and continuously adjusts both the MFC and the outlet valve to maintain the perfect equilibrium.

This system creates a physical "overpressure" on the material's surface, suppressing vaporization. It also provides a medium for convective heating, allowing the gas molecules to carry thermal energy into every nook and cranny of the workpiece, ensuring true temperature uniformity.

The Human Element: Mastering the Process

Partial pressure control elevates the furnace from a passive environment to an active processing tool. This shift, however, demands a higher level of insight and discipline.

The Purity Imperative

When you introduce a gas, its purity is paramount. The gas is your new atmosphere. Any trace impurities like oxygen or moisture are injected directly into the hot zone, defeating the purpose of the vacuum in the first place. The burden of quality shifts from the pump system to the gas supply chain.

From Operator to Process Architect

This is not a "set it and forget it" operation. It requires a deeper understanding of material science. The engineer must architect the process, choosing the right gas, pressure, and temperature profile for the specific alloy and geometry. The mindset shifts from simply removing atmosphere to intentionally constructing one.

The Strategic Choice: When is Emptiness Not Enough?

Deciding whether to use partial pressure is a strategic choice based on your process goals. The table below offers a clear decision framework.

| Scenario | Recommendation | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Processing High-Alloy Materials | Partial Pressure is Essential | Prevents the loss of volatile alloying elements like chromium, manganese, or zinc. |

| Heating Complex or Dense Loads | Partial Pressure is Key | Enables convective heating, ensuring uniform temperature distribution and consistent results. |

| Brazing, Degassing, or Max Purity | Deep Vacuum is Best | The goal is to remove all contaminants; adding a gas would be counterproductive. |

Ultimately, mastering partial pressure is about recognizing that control is more powerful than absence. It transforms a vacuum furnace from a brute-force heating chamber into an instrument of metallurgical precision. For laboratories aiming to master these advanced thermal processes, having equipment with precise, reliable partial pressure control, like the systems offered by KINTEK, is foundational.

If you are ready to move beyond a simple vacuum and achieve a higher level of material integrity and process consistency, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace and Levitation Induction Melting Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Brazing Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

Related Articles

- Why Your Heat-Treated Parts Fail: The Invisible Enemy in Your Furnace

- The Architecture of Emptiness: Achieving Metallurgical Perfection in a Vacuum

- Why Your High-Performance Parts Fail in the Furnace—And How to Fix It for Good

- Why Your High-Temperature Processes Fail: The Hidden Enemy in Your Vacuum Furnace

- Your Vacuum Furnace Hits the Right Temperature, But Your Process Still Fails. Here’s Why.