Heat is a catalyst for transformation. It aligns grain structures, hardens steel, and fuses powders into solids.

But heat is also a catalyst for chaos.

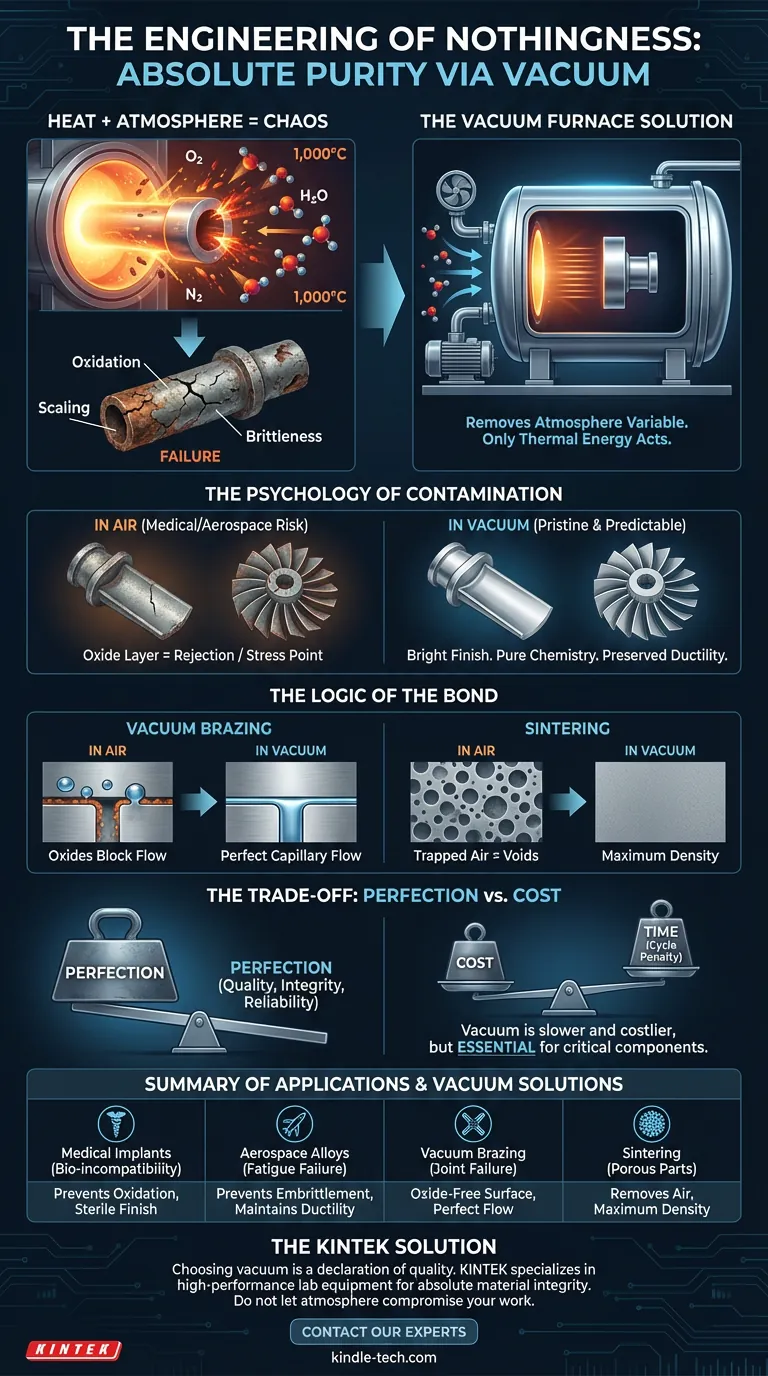

When you heat a material in a standard atmosphere, you are inviting a chemical war. Oxygen, moisture, and nitrogen—benign at room temperature—become aggressive aggressors at 1,000°C. They attack the surface of the metal. They infiltrate the grain boundaries.

The result is oxidation, scaling, and brittleness. In high-stakes engineering, this is known as "failure."

A vacuum furnace is not merely a heater. It is a time capsule. It is a machine designed to remove the variable of the atmosphere so that the only thing acting on the material is thermal energy itself.

Here is why engineers and scientists turn to the vacuum when "good enough" is no longer acceptable.

The Psychology of Contamination

In medicine and aerospace, the margin for error is effectively zero.

Consider a titanium implant meant for the human body, or a superalloy turbine blade in a jet engine. If these materials are heat-treated in air, oxygen reacts with the surface.

This creates an oxide layer.

In a bridge girder, a little rust is a maintenance issue. In a medical implant, surface contamination can lead to rejection by the body. In a turbine blade, an oxide inclusion is a stress concentration point—a crack waiting to happen.

We use vacuum furnaces to create a non-oxidizing environment.

By pumping the air out before the heat turns on, we ensure that:

- Surfaces remain pristine: Parts emerge bright and clean, often requiring no post-processing.

- Chemistry remains pure: No unwanted elements diffuse into the alloy matrix.

- Performance is predictable: Ductility and fatigue resistance are preserved.

The Logic of The Bond: Brazing and Sintering

Beyond protection, a vacuum enables processes that are physically impossible in air.

Vacuum Brazing Brazing involves joining two metals using a liquid filler. For this to work, the filler metal must "wet" the surfaces.

Oxides are the enemy of wetting. They act like oil on water, preventing the flow.

In a vacuum, those oxides are absent. The filler metal flows into the tightest capillaries, creating a joint that is often stronger than the base materials. This is how we build high-performance X-ray tubes and intricate heat exchangers.

Sintering This is the alchemy of turning powder into solid. Whether it is ceramic armor or metal injection molding (MIM), you are bonding particles together.

If you trap air between those particles, you create voids. Voids mean weakness. A vacuum ensures the material is dense, solid, and structurally sound.

The Cost of Perfection (The Trade-Offs)

If vacuum processing is superior, why don't we use it for everything?

Because perfection is expensive.

A vacuum furnace is a complex system involving vacuum pumps, water cooling jackets, and precise seal integrity. It consumes more energy and takes more time.

The Cycle Time Penalty You cannot just open the door and throw a part in.

- You must seal the chamber.

- You must pump it down to high vacuum (which takes time).

- You heat, treat, and then often backfill with inert gas to cool.

For a lug nut on a truck, this is overkill. An atmospheric furnace is faster and cheaper.

But for a critical component, the cost of the furnace is negligible compared to the cost of failure.

Summary of Applications

We choose the tool based on the consequence of the outcome.

| Application | The Risk | The Vacuum Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Implants | Bio-incompatibility / Surface scaling | Prevents oxidation; ensures sterile, bright finish. |

| Aerospace Alloys | Fatigue failure at altitude | Prevents embrittlement; maintains ductility. |

| Vacuum Brazing | Joint failure / Leakage | Ensures oxide-free surface for perfect capillary flow. |

| Sintering | Porous, weak parts | Removes trapped air for maximum density. |

The KINTEK Solution

Choosing a vacuum furnace is a declaration that quality is your primary metric. It is an investment in environmental control for applications where material integrity must be absolute.

At KINTEK, we understand this trade-off. We specialize in the high-performance lab equipment that researchers and engineers rely on when the atmosphere is the enemy.

Whether you are sintering advanced ceramics or brazing complex assemblies, our vacuum furnaces provide the precise control necessary to engineer the perfect material.

Do not let the atmosphere compromise your work.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1700℃ Controlled Atmosphere Furnace Nitrogen Inert Atmosphere Furnace

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 1200℃ Controlled Atmosphere Furnace Nitrogen Inert Atmosphere Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Laboratory High Pressure Vacuum Tube Furnace

Related Articles

- Why Your Brazed Joints Keep Failing: The Invisible Saboteur in Your Furnace

- The Silent Saboteur in Your Furnace: Why Your Heat Treatment Fails and How to Fix It

- Exploring the Using a Chamber Furnace for Industrial and Laboratory Applications

- The Benefits of Controlled Atmosphere Furnaces for Sintering and Annealing Processes

- Atmosphere Furnaces: Comprehensive Guide to Controlled Heat Treatment