The most dangerous moment in a laboratory is rarely during the experiment itself. It is usually immediately after.

There is a psychological urge to declare the work "done" once the data is collected. We rush the shutdown. We neglect the vessel. We treat the furnace tube as a passive background object rather than what it actually is: the primary interface between your sample and the energy that transforms it.

A dirty tube is a variable you didn’t account for. It introduces "ghosts"—cross-contamination from previous runs—that haunt your results.

Cleaning a high-temperature tube, whether quartz or alumina, is not a janitorial task. It is an engineering discipline. It requires the mindset of a surgeon: first, do no harm; second, diagnose before you cut.

The First Principle: Respect the Thermodynamics

Most broken tubes are not dropped. They are shocked.

The physics of thermal expansion are unforgiving. A quartz tube at 200°C looks exactly like a quartz tube at 20°C, but it is in a vastly different energy state. Touching it with a cold tool, a wet cloth, or even the oil from your skin can trigger catastrophic failure.

Before you consider cleaning, you must embrace The Pause.

- Wait for equilibrium: The furnace must be completely cool. Not "cool enough," but ambient room temperature.

- Kill the energy: Disconnect the main power. A heater element activating during disassembly is a disaster.

- Armor up: Heat-resistant gloves and safety glasses are mandatory. You are handling brittle materials that may be under internal stress.

The Diagnostic Phase

You cannot simply "clean" a tube. You must counteract a specific contaminant.

Treating organic residue with a metal brush is ineffective. Treating inorganic film with the wrong acid is destructive. Before you select a method, ask yourself two questions: What is the material of the tube? and What is the nature of the residue?

Scenario A: Loose Debris and "Dust"

- The contaminant: Powders, flakes, or light soot.

- The approach: Low-impact mechanical removal.

- The tool: A soft-bristled brush or a dry cloth on a rod.

- The rule: Never use metal. A steel brush leaves microscopic scratches on quartz. These scratches become "stress risers"—weak points that will eventually crack under vacuum or high heat.

Scenario B: The Organic Ghost

- The contaminant: Carbon deposits, binders, or organic films.

- The approach: Thermal oxidation.

- The method: The "Bake-out."

This is the most elegant solution because it uses the furnace to heal itself. You re-insert the empty tube, introduce a controlled flow of air or oxygen, and ramp the temperature (typically 600–800°C). The heat combusts the carbon, turning the solid residue into gas, leaving the tube pristine.

Scenario C: The Inorganic Stubbornness

- The contaminant: Metallic films or chemical plating.

- The approach: Chemical intervention.

- The method: Solvents and acids.

This is the highest-risk category. You start with the mildest solvent (isopropyl alcohol or acetone). If that fails, you escalate to dilute acids (nitric or hydrochloric).

Crucial Warning: You must know your material science here. Hydrofluoric (HF) acid will eat quartz. Strong bases will destroy alumina. A chemical mismatch doesn't just fail to clean the tube; it dissolves it.

The Invisible Risk: Material Memory

Engineering is the management of trade-offs. Every time you clean a tube, you trade a bit of its lifespan for cleanliness.

If you use wet chemistry (acids or water), you introduce moisture into the microscopic pores of the material. If you heat that tube too quickly afterward, the trapped water turns to steam, expands, and shatters the ceramic structure.

The Post-Clean Protocol:

- Rinse thoroughly with Deionized (DI) water to remove all ionic traces.

- Dry completely. Use a low-temperature drying oven.

- Inspect for scratches or cracks before re-installation.

Summary of Protocols

We have simplified the decision matrix into the table below. Use this to select your path.

| Contaminant Type | Primary Strategy | The "Why" | Key Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loose Powder | Mechanical (Soft) | Physically pushes debris out. | Abrasion: Metal tools cause stress fractures. |

| Organics / Carbon | Thermal Bake-out | Combusts residue into gas. | Overheating: Stay below the tube’s softening point. |

| Inorganic Films | Chemical Wash | Dissolves the bond chemically. | Incompatibility: Wrong acid destroys the tube matrix. |

The KINTEK Standard

In the end, a furnace tube is a consumable, but it should not be a disposable.

Proper maintenance extends the life of your equipment and, more importantly, ensures the integrity of your data. However, when a tube inevitably reaches the end of its lifecycle—due to thermal fatigue or etching—the quality of the replacement matters.

At KINTEK, we don't just sell lab equipment; we understand the physics of the materials we provide. Whether you need high-purity quartz, rugged alumina, or guidance on the specific chemical compatibility of your process, our experts are engineers first and salespeople second.

Do not let a compromised tube be the variable that ruins your work.

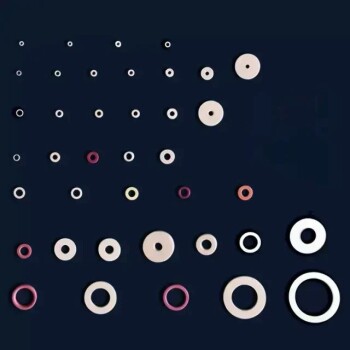

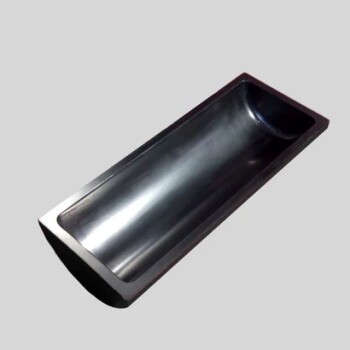

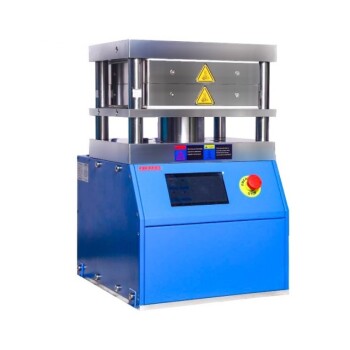

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1400℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- Engineering Advanced Fine Ceramics Aluminium Oxide Al2O3 Ceramic Washer for Wear-Resistant Applications

- Advanced Engineering Fine Ceramics Low Temperature Alumina Granulation Powder

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine for Lamination and Heating

- Carbon Graphite Boat -Laboratory Tube Furnace with Cover

Related Articles

- Beyond the Spec Sheet: The Hidden Physics of a Tube Furnace's True Limit

- Your Tube Furnace Is Not the Problem—Your Choice of It Is

- Beyond Heat: The Tube Furnace as a Controlled Micro-Environment

- High Pressure Tube Furnace: Applications, Safety, and Maintenance

- The Glass Ceiling: Navigating the True Thermal Limits of Quartz Tube Furnaces