Heat is usually associated with chaos. A fire burns; an engine explodes; a star collapses.

But in the laboratory, heat is an instrument of precision. It is the tool we use to rearrange the atomic structure of materials, turning the weak into the strong and the brittle into the resilient.

To do this without destroying the material, we have to remove the one thing that fire needs to breathe: Air.

A vacuum furnace is a contradiction. It is a vessel of extreme violence (heat) contained within a vessel of absolute nothingness (vacuum), all wrapped in a jacket of ice-cold protection (water cooling).

Here is the engineering logic behind how we create fire in a void.

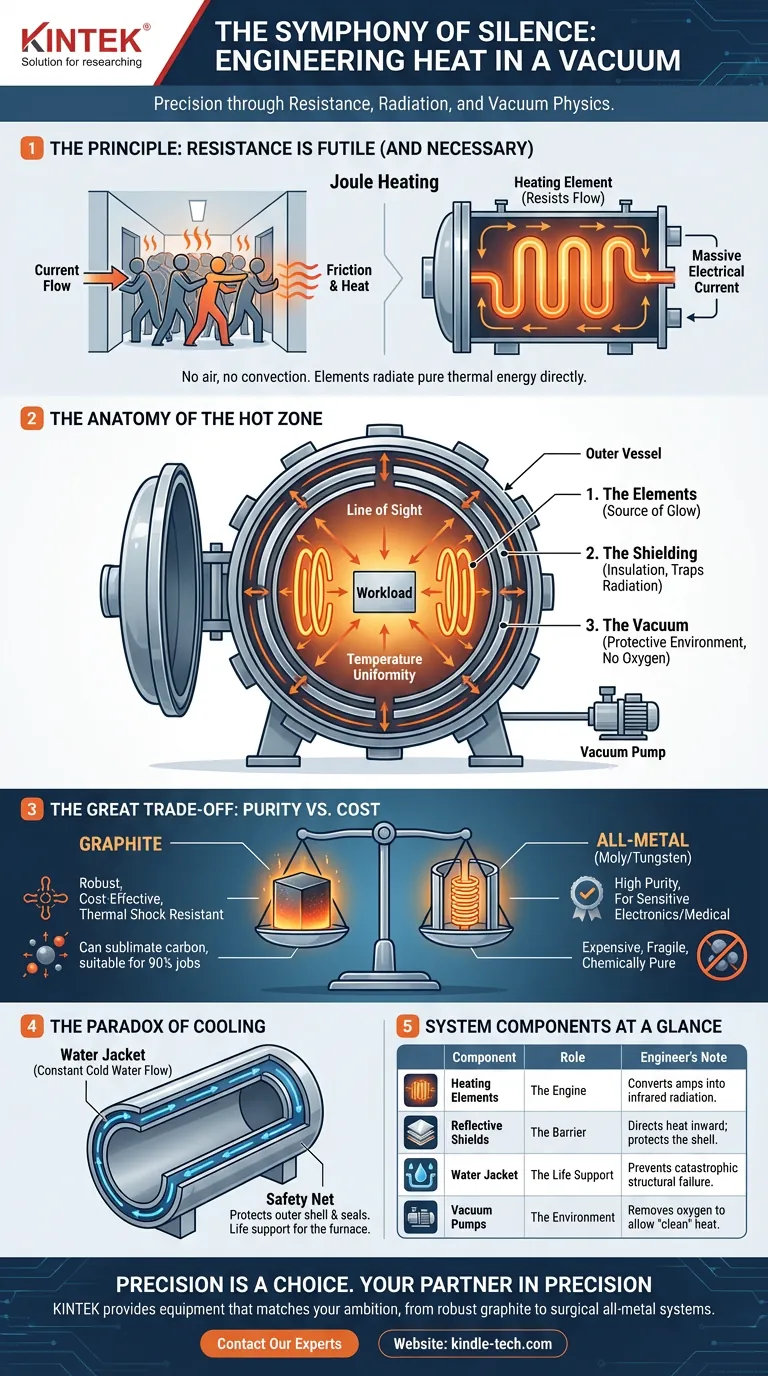

The Principle: Resistance is Futile (and Necessary)

A vacuum furnace does not burn fuel. Burning requires oxygen, and oxygen is the enemy of high-performance metallurgy.

Instead, the system relies on Joule heating.

Think of a narrow hallway crowded with people. If you try to run through it, you create friction. That friction creates heat.

In a vacuum furnace, we force a massive electrical current through a material that resists it. This component—the heating element—fights the flow of electricity. The byproduct of this struggle is thermal energy.

Because there is no air to carry the heat away (convection), the element glows. It radiates pure thermal energy directly onto your workload. It is silent, clean, and incredibly efficient.

The Anatomy of the Hot Zone

The "hot zone" is where the magic happens. It is a carefully engineered stage designed to manage the physics of radiation.

It consists of three critical players:

- The Elements: The source of the glow.

- The Shielding: The insulation that traps the radiation.

- The Vacuum: The protective environment.

In the absence of air, heat travels only by "line of sight." If the heating element cannot "see" the part, the part will not get hot. This requires a layout that surrounds the workload completely, ensuring temperature uniformity.

The Materials of Construction

You cannot use just any metal to build a heater that operates at 2,000°C. The heating elements themselves must be engineered to survive the environment they create.

- Graphite: The workhorse. It is robust, cost-effective, and handles extreme thermal shock.

- Molybdenum (Moly): The specialist. It is used when carbon contamination is a non-starter (common in aerospace and medical applications).

- Ceramics (SiC): The hybrid. Often used in specific oxidation-prone scenarios.

The Great Trade-Off

Engineering is rarely about choosing the "best" option. It is about choosing the right compromise.

When selecting a heating system for a vacuum furnace, you are balancing purity against cost.

The Graphite Path

Graphite is the standard. It is strong and gets stronger as it heats up. However, in the microscopic world, graphite can sublimate. It releases carbon atoms into the vacuum. For 90% of brazing and heat-treating jobs, this is irrelevant.

The All-Metal Path

For sensitive electronics or medical implants, a rogue carbon atom is a defect. Here, we must use an All-Metal Hot Zone. We use Molybdenum or Tungsten elements and shields. They are expensive. They are fragile. But they are chemically pure.

The Paradox of Cooling

The most critical part of a heating system is actually the cooling system.

The entire hot zone sits inside a double-walled steel vessel. Between those walls flows a constant stream of cold water.

This is the safety net. It keeps the outer shell cool to the touch and prevents the vacuum seals from melting. If the water stops, the furnace destroys itself. It is a system that relies on the balance between extreme heat inside and constant cooling outside.

System Components at a Glance

| Component | Role | The Engineer's Note |

|---|---|---|

| Heating Elements | The Engine | Converts amps into infrared radiation. |

| Reflective Shields | The Barrier | Directs heat inward; protects the shell. |

| Water Jacket | The Life Support | Prevents catastrophic structural failure. |

| Vacuum Pumps | The Environment | Removes oxygen to allow "clean" heat. |

Precision is a Choice

The difference between a failed experiment and a breakthrough material often comes down to the quality of the thermal cycle.

Did the temperature fluctuate? Did oxygen leak in? Did carbon migrate where it shouldn't have?

These are not just operational details; they are the variables that define your success. Understanding the heating mechanism allows you to stop fighting the furnace and start controlling the outcome.

Your Partner in Precision

At KINTEK, we understand that a vacuum furnace is not just a box that gets hot. It is a complex ecosystem of resistance, radiation, and vacuum physics.

Whether you need the robust reliability of a graphite hot zone or the surgical purity of an all-metal system, we provide the equipment that matches your ambition. We specialize in the lab equipment and consumables that ensure your "line of sight" is always clear.

Do not leave your materials to chance.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine Heated Vacuum Press

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Heated Vacuum Press Machine Tube Furnace

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Furnace for Heat Treat and Sintering

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

Related Articles

- From Dust to Density: The Microstructural Science of Hot Pressing

- The Pressure Paradox: Why More Isn't Always Better in Hot Press Sintering

- The Physics of Impossible Shapes: Why Hot Stamping Redefined High-Strength Steel

- Beyond Heat: Why Pressure is the Deciding Factor in Advanced Materials

- Beyond Heat: How Pressure Forges Near-Perfect Materials