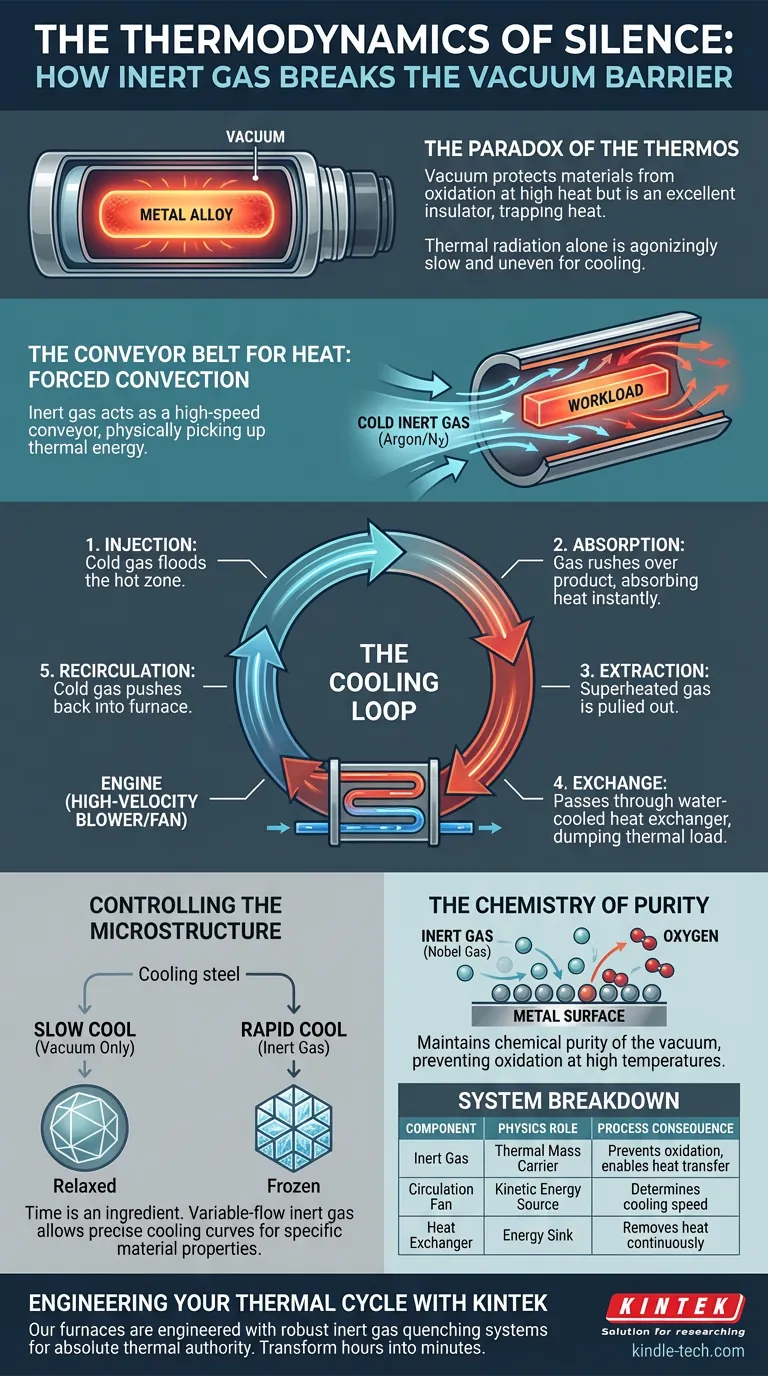

The Paradox of the Thermos

There is a fundamental contradiction in high-temperature processing.

To protect advanced materials, we heat them in a vacuum. By removing air, we remove oxygen, ensuring the metal doesn't burn or tarnish. We create a perfect, silent void.

But a vacuum is also the world’s best insulator. It is a thermos bottle. It is designed to keep heat in.

This creates a physics problem. Once your cycle is finished and your alloy has reached 1,200°C, how do you cool it down?

If you rely on thermal radiation—simply waiting for the heat to drift away in the void—the process is agonizingly slow. It is also uneven. The edges cool while the core stays molten. For sensitive metallurgy, this variance is catastrophic.

To solve this, engineers have to break the vacuum without breaking the chemistry.

They use Inert Gas Technology.

The Conveyor Belt for Heat

We often think of inert gases (like Argon or Nitrogen) merely as shields—a protective blanket to stop oxidation.

But in a modern quenching furnace, the gas is not a shield. It is a vehicle.

The system works on the principle of Forced Convection. Because a vacuum cannot conduct heat, we introduce a medium that can. The gas acts as a high-speed conveyor belt, physically picking up thermal energy from the workload and carrying it away.

The Cooling Loop

The architecture of this system is circular and aggressive. It relies on three mechanical pillars:

- The Medium: High-purity gas enters the chamber. It does not react with the metal; it only touches it.

- The Engine: A high-velocity blower or fan drives the gas.

- The Sink: A water-cooled heat exchanger strips the energy from the gas.

The cycle happens in seconds:

- Injection: Cold gas floods the hot zone.

- Absorption: The gas rushes over the refractory material and the product, absorbing heat instantly.

- Extraction: The now-superheated gas is pulled out of the chamber.

- Exchange: It passes through the heat exchanger, dumping its thermal load into cooling water.

- Recirculation: The gas, now cold again, is pushed back into the furnace to repeat the job.

Controlling the Microstructure

Why go to this trouble? Why is "fast" better than "slow"?

In metallurgy, time is an ingredient.

The physical properties of an alloy—its hardness, its ductility, its strength—are often locked in during the cooling phase. This is known as quenching.

If you cool steel slowly, the crystalline structure relaxes. It becomes soft. If you cool it rapidly, you freeze the structure in a specific state, making it hard.

A vacuum furnace without inert gas cooling is a blunt instrument. It can only heat. It cannot control the descent.

With a variable-flow inert gas system, an operator can dial in the exact cooling curve required by the recipe. You are no longer waiting for physics to happen; you are commanding it.

The Chemistry of Purity

There is a second, equally critical reason for this closed-loop system: Oxidation.

At high temperatures, metals are chemically desperate to bond with oxygen. Even a trace amount of air introduced during cooling would instantly ruin a batch of titanium or aerospace superalloys.

By using noble gases like Argon, we maintain the chemical purity of the vacuum while gaining the thermal conductivity of a fluid.

System Breakdown

Here is how the components translate to process outcomes:

| Component | Physics Role | Process Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Inert Gas (Argon/N2) | Thermal Mass Carrier | Prevents oxidation; enables heat transfer in a void. |

| Circulation Fan | Kinetic Energy Source | Determines the speed of cooling (Quench Rate). |

| Heat Exchanger | Energy Sink | Removes heat from the system continuously. |

Active vs. Passive Systems

It is important to distinguish this from the furnace's heating control.

The heating elements maintain a "soak" temperature. They pulse on and off to keep the line flat. That is maintenance.

Inert gas cooling is active intervention. It requires heavy hardware—massive fans, complex plumbing, and heat exchangers. It adds cost and complexity.

However, it transforms the furnace from a simple oven into a precision metallurgical instrument. It allows you to turn hours of cooling time into minutes, doubling or tripling production throughput while hitting material specs that passive cooling simply cannot achieve.

Engineering Your Thermal Cycle

The choice to implement inert gas technology is rarely a choice of preference; it is a choice dictated by the physics of your material.

If you need speed, you need gas. If you need specific hardness, you need controlled flow. If you need purity, you need a sealed loop.

At KINTEK, we understand that the cooling phase is just as critical as the heating phase. Our high-temperature vacuum furnaces are engineered with robust inert gas quenching systems designed to give you absolute authority over the thermal environment.

Whether you are developing new alloys or scaling up production, Contact Our Experts to discuss how we can refine your thermal processing strategy.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory High Pressure Vacuum Tube Furnace

- Laboratory Rapid Thermal Processing (RTP) Quartz Tube Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Molybdenum Wire Sintering Furnace for Vacuum Sintering

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Heated Vacuum Press Machine Tube Furnace

- 1700℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

Related Articles

- The Silent Boundary: Engineering the Heart of the Tube Furnace

- Introducing the Lab Vacuum Tube Furnaces

- The Architecture of Heat: Why Precision is the Only Variable That Matters

- The Architecture of Emptiness: How Vacuum Tube Furnaces Defy Entropy

- The Silent Partner in Pyrolysis: Engineering the Perfect Thermal Boundary