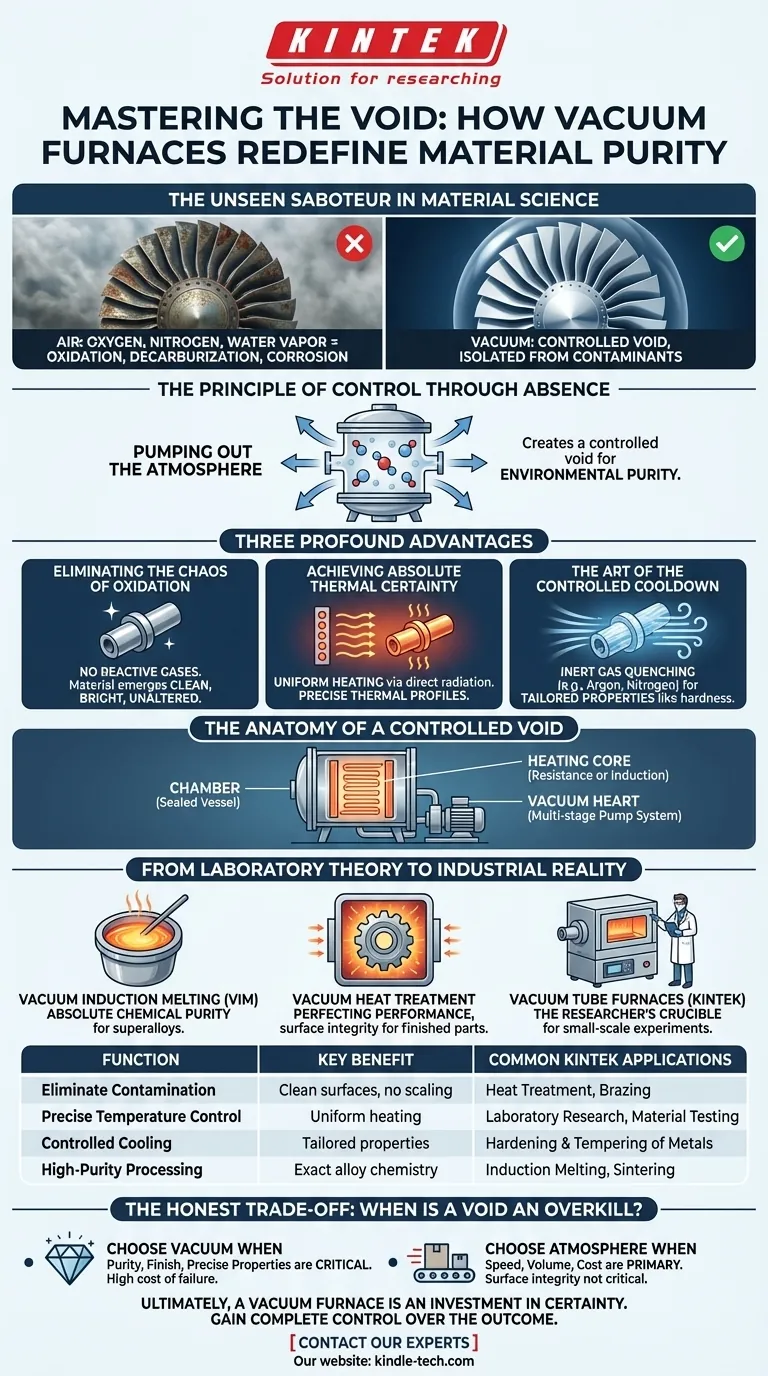

The Unseen Saboteur in Material Science

Imagine a team of engineers crafting a critical turbine blade. They’ve perfected the alloy chemistry, calculated the thermal profile to the exact degree, and initiated the heat treatment process.

Yet, the final component fails quality control. The surface is covered in a fine scale, its carbon content is depleted, and its structural integrity is compromised.

The culprit wasn’t a flaw in the metal or the temperature. It was the air itself. At high temperatures, the oxygen, nitrogen, and water vapor we breathe become aggressive saboteurs, triggering unwanted chemical reactions that degrade even the most robust materials. This is the fundamental problem that drives the need for a more controlled environment.

The Principle of Control Through Absence

The genius of a vacuum furnace isn't what it adds, but what it removes. By pumping out the atmosphere, it creates a controlled void—an environment where the material is isolated from unpredictable external influences.

This isn’t just about heating. It's about achieving a state of environmental purity where the only changes to the workpiece are the ones you intentionally introduce. This philosophy of "control through absence" provides three profound advantages.

1. Eliminating the Chaos of Oxidation

In a conventional furnace, heat and oxygen combine to cause oxidation (scaling) and decarburization (carbon loss). This is a form of high-temperature corrosion that weakens the material from the outside in.

A vacuum prevents this entirely. With no reactive gases present, the material emerges from the furnace clean, bright, and chemically unaltered. Its surface integrity is a perfect reflection of its internal purity.

2. Achieving Absolute Thermal Certainty

Air creates convection currents, leading to tiny temperature fluctuations and uneven heating. In a vacuum, heat transfer occurs primarily through direct radiation from the heating elements.

This allows for incredibly uniform heating and precise execution of thermal profiles—specific ramp rates, soak times, and cooling sequences. It removes the randomness, ensuring every part of the component experiences the exact same thermal journey.

3. The Art of the Controlled Cooldown

The process doesn't end when the heat is turned off. Cooling—or quenching—is what locks in the final properties of a material, like hardness and strength.

A vacuum furnace allows for controlled quenching by backfilling the chamber with a high-pressure stream of an inert gas like argon or nitrogen. This rapidly and evenly extracts heat, providing a level of control that simply letting a part "air cool" can never match.

The Anatomy of a Controlled Void

Creating and maintaining this pristine environment requires a system of specialized components working in perfect concert.

- The Chamber: A robust, sealed vessel, often with water-cooled double walls, acts as a fortress against the external atmosphere.

- The Heating Core: The engine of the furnace. This can be resistance heating, using graphite or refractory metal elements, or electromagnetic induction heating, which generates heat directly within the workpiece itself for exceptionally clean melting.

- The Vacuum Heart: A multi-stage pump system—starting with mechanical pumps and finishing with high-vacuum diffusion or Roots pumps—works to achieve pressures as low as 7×10⁻³ Pa, a near-perfect vacuum.

From Laboratory Theory to Industrial Reality

The application of vacuum technology is tailored to the specific goal, whether it's creating a new alloy from scratch or perfecting an existing component.

Forging Flawless Alloys: Vacuum Induction Melting

When the goal is absolute chemical purity, a vacuum induction furnace is the standard. It melts metals in a crucible within the vacuum, preventing the molten pool from reacting with any gases. This is essential for producing the high-purity superalloys used in aerospace and medical implants.

Perfecting Material Performance: Vacuum Heat Treatment

This is the art of enhancing a finished part. Processes like hardening, annealing, and brazing are performed in a vacuum to ensure that the treatment improves the material's bulk properties without degrading its surface.

The Researcher's Crucible: Vacuum Tube Furnaces

In a laboratory setting, researchers need versatility and precision to test new materials and processes. A vacuum tube furnace, like those offered by KINTEK, provides an ideal platform for small-scale experiments, enabling scientists to explore material behavior in a perfectly controlled environment without the scale of an industrial unit.

| Function | Key Benefit | Common KINTEK Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Eliminate Contamination | Clean, bright surfaces; no scaling or decarburization. | Heat Treatment, Brazing, Annealing |

| Precise Temperature Control | Uniform heating and exact thermal profiles. | Laboratory Research, Material Testing |

| Controlled Cooling | Tailored material properties like hardness. | Hardening & Tempering of Metals |

| High-Purity Processing | Exact alloy chemistry; dense, strong sintered parts. | Induction Melting, Sintering |

The Honest Trade-Off: When is a Void an Overkill?

For all its power, a vacuum furnace is a specialized instrument. Its complexity, higher initial cost, and longer cycle times (due to pump-down) make it unnecessary for every application.

The choice is a matter of intent:

- Choose Vacuum When: Material purity, surface finish, and precise metallurgical properties are non-negotiable. The cost of failure is high.

- Choose Atmosphere When: Speed, volume, and cost are the primary drivers, and the material's surface integrity is not a critical performance factor.

Ultimately, a vacuum furnace is the definitive tool when you must be the sole author of your material's final properties. It is an investment in certainty. By removing the unpredictable variable of the atmosphere, you gain complete control over the outcome.

Whether you are pioneering new alloys in a research setting or perfecting critical components for industrial use, achieving this level of control is fundamental to success. For any thermal process where the environment cannot be left to chance, the solution is to master the void.

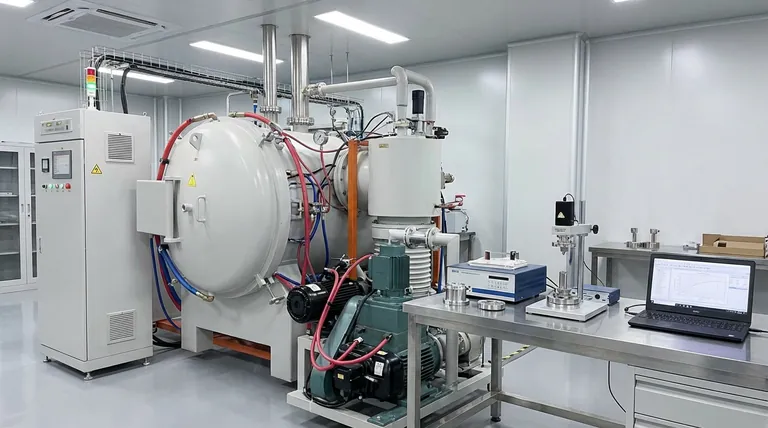

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace and Levitation Induction Melting Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Graphite Vacuum Furnace High Thermal Conductivity Film Graphitization Furnace

Related Articles

- How Vacuum Induction Melting Outperforms Traditional Methods in Advanced Alloy Production

- How Vacuum Induction Melting Ensures Unmatched Reliability in Critical Industries

- How Vacuum Induction Melting (VIM) Transforms High-Performance Alloy Production

- Your Furnace Hit the Right Temperature. So Why Are Your Parts Failing?

- The Symphony of Silence: Molybdenum and the Architecture of the Vacuum Hot Zone