The Violence of Heat

When you heat a metal, you are not just changing its temperature. You are changing its personality.

At room temperature, steel and titanium are stable. But add extreme thermal energy, and they become chemically desperate. They yearn to bond with oxygen. They seek out carbon.

In a standard room, the air is filled with reactive elements waiting to attack the surface of your material. The result is oxidation (scaling) or decarburization. The metal comes out weaker and uglier than it went in.

This is the central problem of heat treatment: How do you protect a material at its most vulnerable moment?

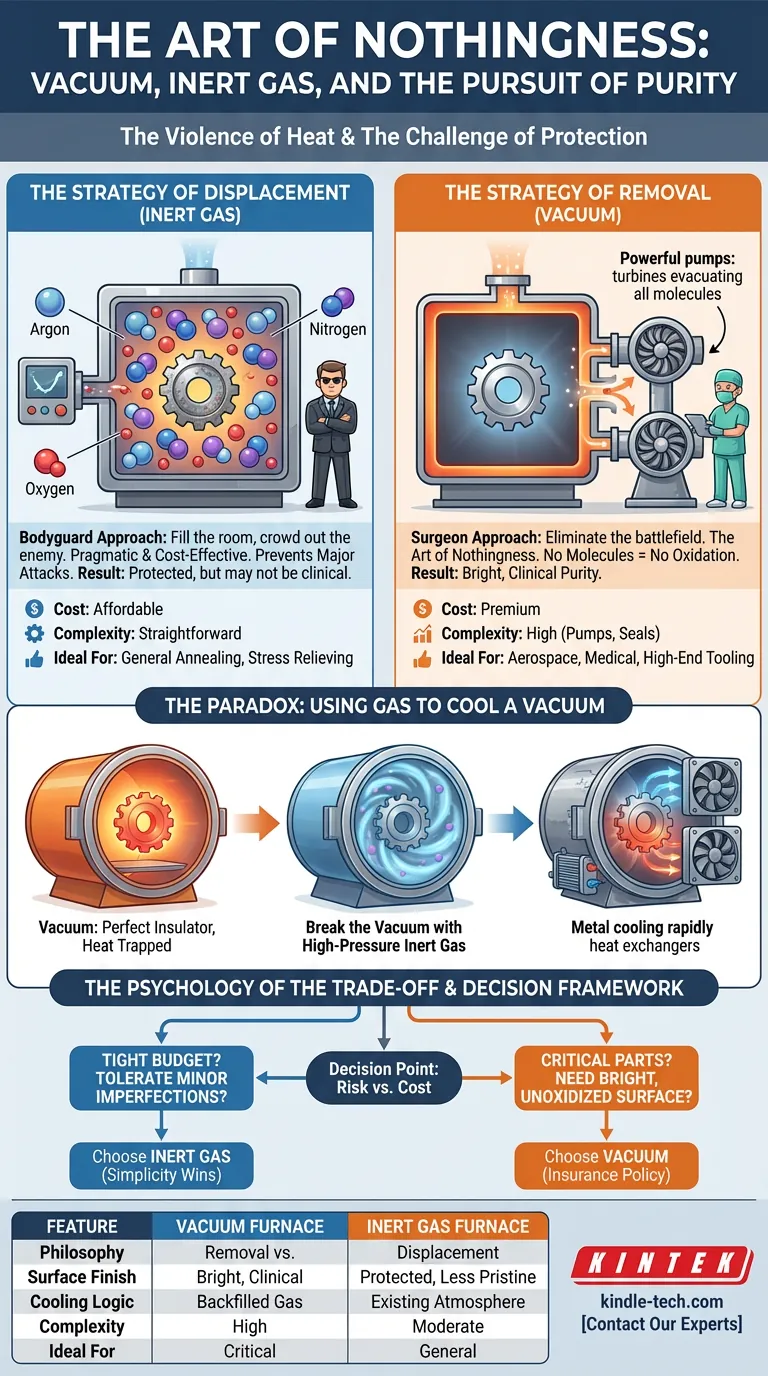

There are two primary schools of thought. One is to crowd out the enemy. The other is to remove the battlefield entirely.

The Strategy of Displacement (Inert Gas)

The first strategy is the Inert Gas Furnace.

Think of this as a bodyguard approach. You cannot empty the room of air, so you fill it with something else—something that refuses to fight.

You pump the furnace chamber full of Argon or Nitrogen. These non-reactive gases displace the oxygen, blanketing your workpiece in a protective fog.

It is effective. It prevents the major chemical attacks.

It is also pragmatic.

- Cost: It is generally affordable.

- Complexity: The machinery is straightforward.

- Result: It prevents scaling, though it may not achieve clinical perfection.

For general annealing or stress relieving where "good enough" is acceptable, displacement is the logical economic choice.

The Strategy of Removal (Vacuum)

The second strategy is the Vacuum Furnace.

This is the approach of the surgeon. You don't just cover up the contaminants; you eliminate them.

Using powerful pumps, a vacuum furnace evacuates the chamber, physically removing air molecules until the pressure drops to near-space levels.

The result is "The Art of Nothingness."

Because there are no molecules to react with, there is no oxidation. None. The part emerges from the furnace with a "bright" surface finish—often cleaner than when it went in.

This purity is non-negotiable for high-stakes industries:

- Aerospace components.

- Medical implants.

- High-end tool steels.

If the cost of failure is high, you pay the premium for the vacuum.

The Paradox: Using Gas to Cool a Vacuum

Here is where the engineering gets romantic, and where most confusion arises.

A vacuum is a perfect insulator. A thermos flask works on this principle. If there is no air, heat cannot travel by convection. It stays trapped in the metal.

This is great for efficiency during heating. It is a disaster for cooling.

In metallurgy, how you cool (quench) is often more important than how you heat. To harden steel, you need to cool it violently fast to freeze the microstructure in place.

So, how do you cool something rapidly in a vacuum that acts like a thermos?

You break the vacuum.

In modern vacuum furnaces, once the heating cycle is done, the system rapidly backfills the chamber with high-pressure inert gas. Powerful fans circulate this gas through heat exchangers, stripping the heat away from the metal.

This gives you the best of both worlds:

- Heating: The absolute purity of a vacuum.

- Cooling: The speed and control of gas quenching.

The Psychology of the Trade-off

Choosing between a standard inert gas furnace and a vacuum furnace is rarely a technical impossibility. It is usually a psychological calculation of risk versus cost.

A vacuum furnace is a complex beast. It requires robust chambers, high-performance seals, and sophisticated pumping systems. It is expensive to buy and slower to cycle (pumping down takes time).

An inert gas furnace is simpler, faster, and cheaper.

How do you choose?

The Decision Framework

- Choose Vacuum if: You need a bright, unoxidized surface without post-processing. If you are working with reactive alloys (Titanium) or critical medical/aerospace parts, the premium is an insurance policy you must buy.

- Choose Inert Gas if: You are doing general oxidation protection. If your budget is tight and you can tolerate minor surface imperfections, simplicity wins.

- Choose Active Atmosphere if: You actually want a reaction (like carburizing or nitriding). Neither vacuum nor inert gas will help you there; you need reactive gases to change the surface chemistry.

Summary: The Engineering Trade-offs

| Feature | Vacuum Furnace | Inert Gas Furnace |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | Removal: Eliminate the atmosphere entirely. | Displacement: Replace air with non-reactive gas. |

| Surface Finish | Bright, clean, clinical purity. | Protected, but less pristine than vacuum. |

| Cooling Logic | Uses backfilled gas to break the insulating vacuum. | Uses the existing atmosphere to cool. |

| Complexity | High (Pumps, seals, pressure vessels). | Moderate (Gas flow controls). |

| Ideal For | Aerospace, Medical, Critical Tooling. | General Heat Treatment, Budget-Conscious Labs. |

Precision is a Choice

There is no "better" furnace, only the right tool for the specific metallurgical goal.

Whether you need the clinical silence of a vacuum or the pragmatic protection of an argon blanket, the goal is always control. Control over the heat, and control over the reaction.

At KINTEK, we specialize in the equipment that gives you that control. From high-vacuum systems to robust inert gas solutions, we help laboratories navigate the trade-offs to find the perfect thermal processing solution.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Brazing Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Molybdenum Wire Sintering Furnace for Vacuum Sintering

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace with 9MPa Air Pressure

Related Articles

- Why Your Heat-Treated Parts Fail: The Invisible Enemy in Your Furnace

- The Architecture of Emptiness: Achieving Metallurgical Perfection in a Vacuum

- The Engineering of Nothingness: Why Vacuum Furnaces Define Material Integrity

- Your Vacuum Furnace Hits the Right Temperature, But Your Process Still Fails. Here’s Why.

- Why Your High-Performance Parts Fail in the Furnace—And How to Fix It for Good