The Seduction of Extremes

There is a natural human instinct in engineering to chase the edges of the chart. We want the fastest processor, the strongest steel, the deepest ocean.

In the world of thermal processing, this instinct manifests as a desire for the highest possible vacuum. The logic seems sound: if air is the enemy—bringing oxidation and contamination—then surely the total absence of air is the ultimate solution.

But in the physics of materials, "more" is not always "better." Sometimes, "more" is destructive.

The critical insight in selecting a vacuum furnace is not to pursue the deepest void possible. It is to understand the precise environment your material requires to thrive.

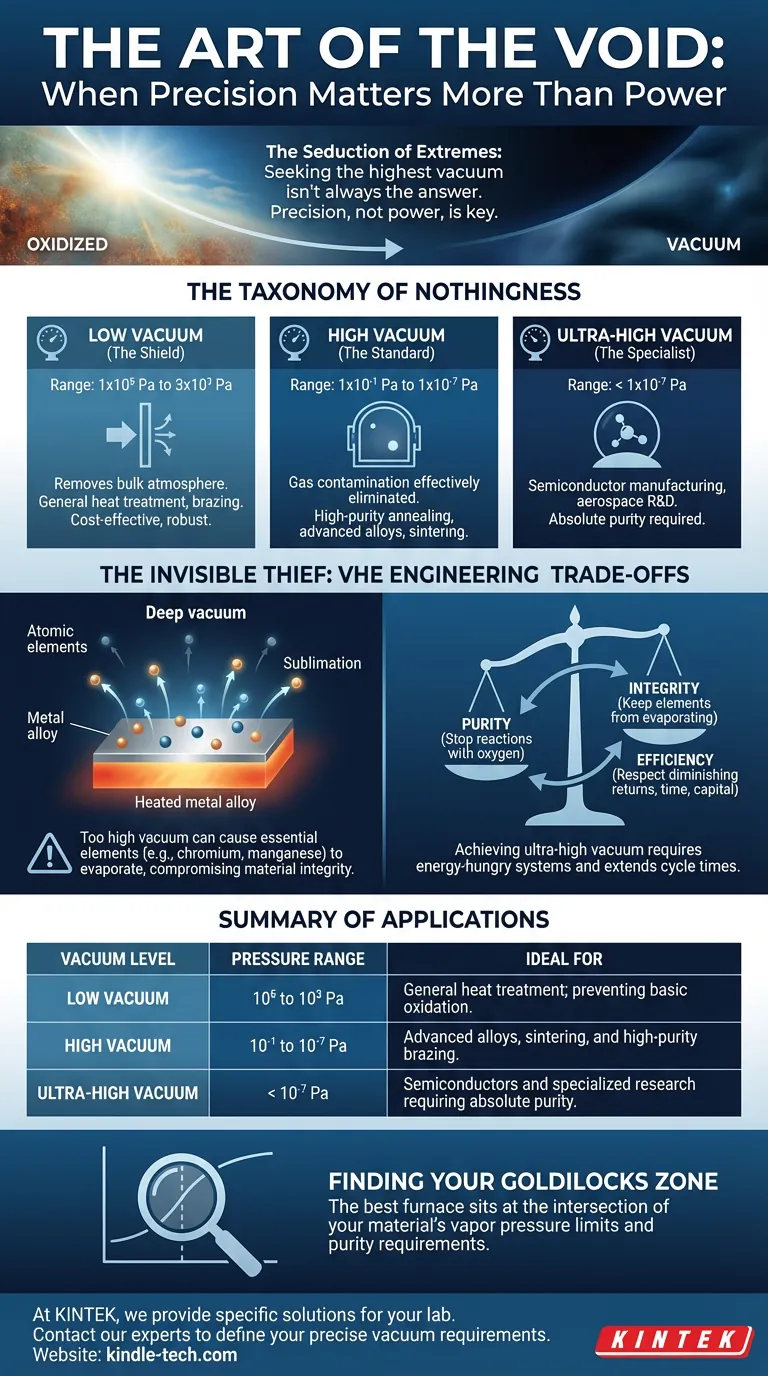

The Taxonomy of Nothingness

To understand the tool, we must first measure the emptiness.

A vacuum furnace is defined not by how hot it gets, but by the minimum pressure it can reliably maintain. We categorize these systems into three distinct tiers, measured in Pascals (Pa). Each tier represents a different level of technological complexity and a different philosophy of protection.

1. Low Vacuum (The Shield)

Range: 1×10⁵ Pa down to 3×10³ Pa

Think of low vacuum not as a void, but as a clean room. It removes the bulk of the atmosphere.

These furnaces are the workhorses for general heat treatment and brazing. If your goal is simply to prevent heavy oxidation on standard materials, this is your solution. It is cost-effective, robust, and sufficient.

2. High Vacuum (The Standard)

Range: 1×10⁻¹ Pa down to 1×10⁻⁷ Pa

This is where the vast majority of modern metallurgy lives. At this level, gas contamination is effectively eliminated.

High vacuum systems are essential for:

- High-purity annealing.

- Vacuum brazing of advanced alloys.

- Sintering sensitive materials.

3. Ultra-High Vacuum (The Specialist)

Range: < 1×10⁻⁷ Pa

This is the realm of semiconductor manufacturing and aerospace R&D. Here, even a stray molecule is a threat. These systems are marvels of engineering, designed for materials where purity is the only metric that matters.

The Invisible Thief: Vapor Pressure

Why not simply buy an Ultra-High Vacuum furnace for everything, just to be safe?

Because of a physical phenomenon called vapor pressure.

Every element has a tipping point. As you heat a material, its atoms vibrate with increasing energy. If the pressure surrounding that material drops too low (the vacuum becomes too deep), the atoms at the surface simply let go.

They don't melt. They sublimate. They turn directly from solid to gas and vanish into the vacuum pump.

If you place a complex alloy in a vacuum that is too high for its specific chemistry, you might successfully prevent oxidation, but you might also boil off essential alloying elements like chromium or manganese.

The result is a part that looks perfect on the outside but has been chemically hollowed out on the inside. Its mechanical properties are ruined, not by contamination, but by over-processing.

The Engineering Trade-Offs

Selecting a vacuum furnace is a balancing act between three competing forces:

- Purity: You need a vacuum deep enough to stop reactions with oxygen.

- Integrity: You need enough pressure to keep your alloy's elements from evaporating.

- Efficiency: You need to respect the laws of diminishing returns.

Achieving high or ultra-high vacuum requires sophisticated, energy-hungry multi-stage pump systems (like turbomolecular pumps). It extends cycle times significantly as the system fights to remove those last few molecules.

If your process doesn't require it, you are paying a premium in time and capital to potentially damage your own product.

Summary of Applications

Here is a quick guide to matching the void to the value:

| Vacuum Level | Pressure Range | Ideal For |

|---|---|---|

| Low Vacuum | 10⁵ to 10³ Pa | General heat treatment; preventing basic oxidation. |

| High Vacuum | 10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁷ Pa | Advanced alloys, sintering, and high-purity brazing. |

| Ultra-High Vacuum | < 10⁻⁷ Pa | Semiconductors and specialized research requiring absolute purity. |

Finding Your Goldilocks Zone

The "best" furnace is not the one with the most impressive spec sheet. It is the one that sits exactly at the intersection of your material's vapor pressure limits and your purity requirements.

It is a decision that requires looking at a phase diagram, not just a price tag.

At KINTEK, we understand that lab equipment is not about generic power; it is about specific solutions. We specialize in navigating these trade-offs. Whether you are working with robust steel or sensitive superalloys, we help you identify the equipment that ensures purity without compromising integrity.

Do not leave your material science to chance. Contact Our Experts to define the precise vacuum requirements for your laboratory today.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Brazing Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

Related Articles

- The Architecture of Emptiness: Achieving Metallurgical Perfection in a Vacuum

- Materials Science with the Lab Vacuum Furnace

- Why Your Brazed Joints Fail: The Truth About Furnace Temperature and How to Master It

- Why Your High-Performance Parts Fail in the Furnace—And How to Fix It for Good

- Your Vacuum Furnace Hits the Right Temperature, But Your Process Still Fails. Here’s Why.