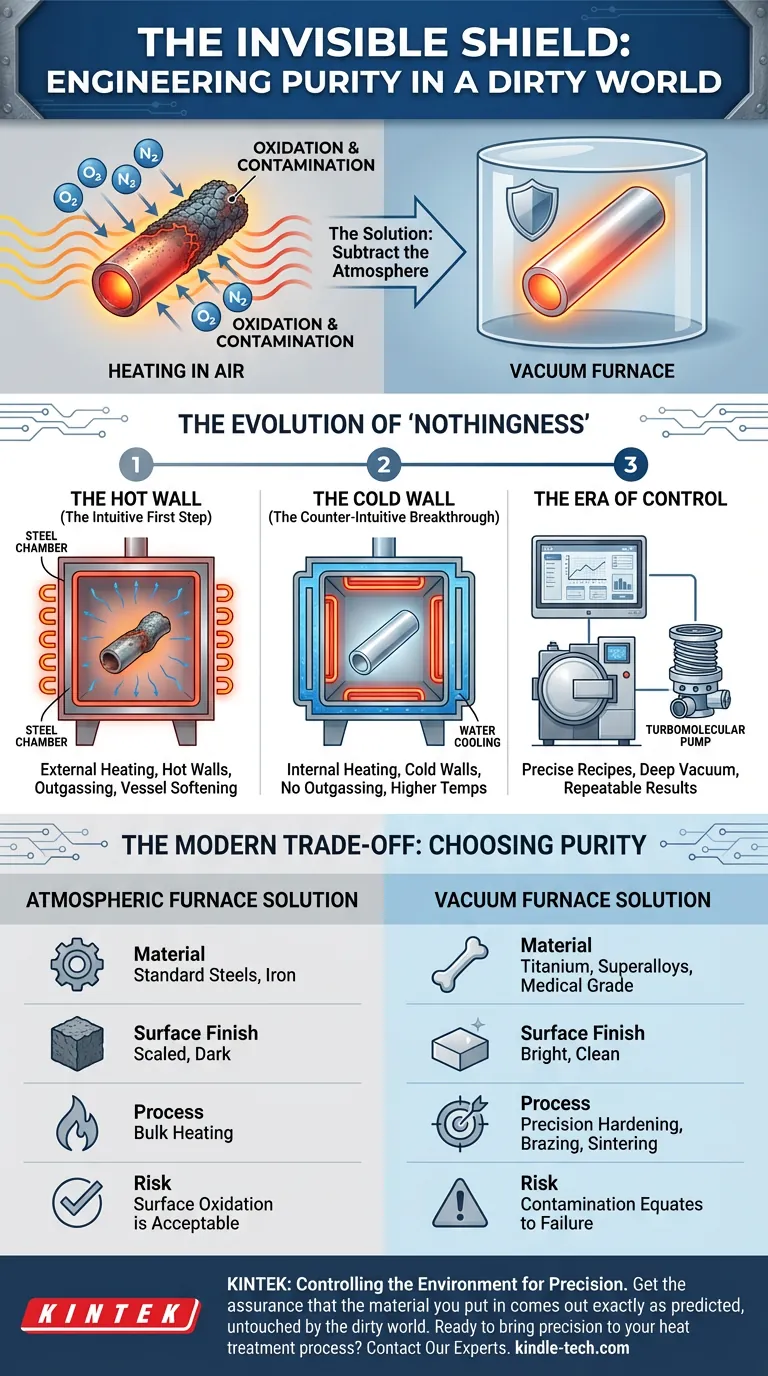

The Invisible Shield: Engineering Purity in a Dirty World

The history of the vacuum furnace is not really about furnaces. It is a story about the relentless human struggle against a fundamental law of nature: contamination.

In the natural world, purity is an anomaly. Most metals want to return to their ore state. They yearn to bind with oxygen.

When you heat a metal, you accelerate this desire. You give the atoms the energy they need to react with the atmosphere. For centuries, this was the metallurgist’s dilemma. To strengthen a metal, you must heat it. But by heating it in the open air, you risk ruining it.

The solution wasn't to change the metal. It was to remove the world around it.

The Enemy is the Atmosphere

In a standard furnace, the air is not empty space; it is a chemical soup.

Nitrogen and oxygen, harmless at room temperature, become aggressive attackers at 1,000°C. They cause oxidation—scaling, rusting, and embrittlement.

For a cast iron skillet, this doesn't matter. But for a jet engine turbine blade or a medical implant, a microscopic layer of oxide is a catastrophic failure waiting to happen.

The engineers of the early 20th century realized that to process the materials of the future, they needed an invisible shield. They didn't add a protective coating. They subtracted the atmosphere.

The Evolution of "Nothingness"

Creating a vacuum—a space devoid of matter—is difficult. Heating that space is even harder.

The journey from early experiments to modern laboratory standards was driven by necessity. The dawn of the nuclear and aerospace ages demanded materials like titanium and zirconium. These metals are so reactive that heating them in air is essentially setting them on fire.

The industry had to evolve, and it did so in three distinct phases.

1. The Hot Wall (The Intuitive First Step)

Early engineers did the logical thing: they built a steel vessel, pumped the air out, and applied heat to the outside of the chamber.

It worked, but it was flawed.

- The chamber walls got hot.

- Hot metal releases trapped gases (outgassing), which contaminated the very vacuum they were trying to create.

- The vessel began to lose strength at high temperatures.

It was a clumsy solution. It was a pressure cooker in reverse.

2. The Cold Wall (The Counter-Intuitive Breakthrough)

Then came the shift that defines modern vacuum technology. Engineers moved the heating elements inside the vacuum chamber.

They surrounded the vacuum vessel with a water-cooling jacket. The walls stayed cold. Only the "hot zone" inside heated up.

This was the "Cold Wall" revolution.

- No outgassing: The cold walls stopped releasing impurities.

- Higher temperatures: The vessel didn't soften, allowing for extreme heat treatment.

- Efficiency: Energy was focused solely on the workload.

This design is the ancestor of almost every high-performance furnace KINTEK supplies today.

3. The Era of Control

Once the structure was perfected, the focus shifted to the brain of the machine.

Early furnaces were "art forms" requiring manual tuning. Today, Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) have turned them into instruments of science. We now have recipes—precise, repeatable sequences of heating, soaking, and cooling.

Coupled with the evolution from oil pumps to clean turbomolecular pumps, we can now achieve vacuum levels that mimic deep space, right on a laboratory bench.

The Modern Trade-off

Why isn't every furnace a vacuum furnace?

Because perfection is expensive. The history of technology is a history of trade-offs.

A vacuum furnace is a complex ecosystem. It requires seals that hold against the weight of the atmosphere. It requires pumps that run at tens of thousands of RPMs. It requires water cooling and precise gas management.

However, for specific applications, the cost of complexity is lower than the cost of failure.

| If you need... | The Atmospheric Furnace Solution | The Vacuum Furnace Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Standard Steels, Iron | Titanium, Superalloys, Medical Grade Steel |

| Surface Finish | Scaled, Dark (Requires cleaning) | Bright, Clean (Ready to use) |

| Process | Bulk heating | Precision hardening, Brazing, Sintering |

| Risk | Surface oxidation is acceptable | Contamination equates to failure |

Leveraging a Century of Innovation

The vacuum furnace is no longer just a tool for the aerospace giants. It has scaled down. It has become accessible to university labs, R&D centers, and small-batch manufacturers.

When you look at a modern vacuum furnace, you are looking at a machine designed to pause entropy. It creates a sanctuary where heat can do its work without the corruption of the air.

At KINTEK, we understand that you aren't just buying a machine with a heater and a pump. You are buying the ability to control the environment. You are buying the assurance that the material you put in comes out exactly as the physics predicted, untouched by the dirty world outside.

Whether you are sintering exotic alloys or requiring a bright finish on medical instruments, the right equipment is the difference between an experiment and a solution.

Ready to bring precision to your heat treatment process?

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Brazing Furnace

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Molybdenum Wire Sintering Furnace for Vacuum Sintering

Related Articles

- Your Furnace Hit the Right Temperature. So Why Are Your Parts Failing?

- Your Vacuum Furnace Hits the Right Temperature, But Your Process Still Fails. Here’s Why.

- The Engineering of Nothingness: Why Vacuum Furnaces Define Material Integrity

- Why Your Heat-Treated Parts Fail: The Invisible Enemy in Your Furnace

- Why Your High-Temperature Processes Fail: The Hidden Enemy in Your Vacuum Furnace