The Sound of Silence

If you stand next to a conventional industrial furnace, you hear it before you feel it.

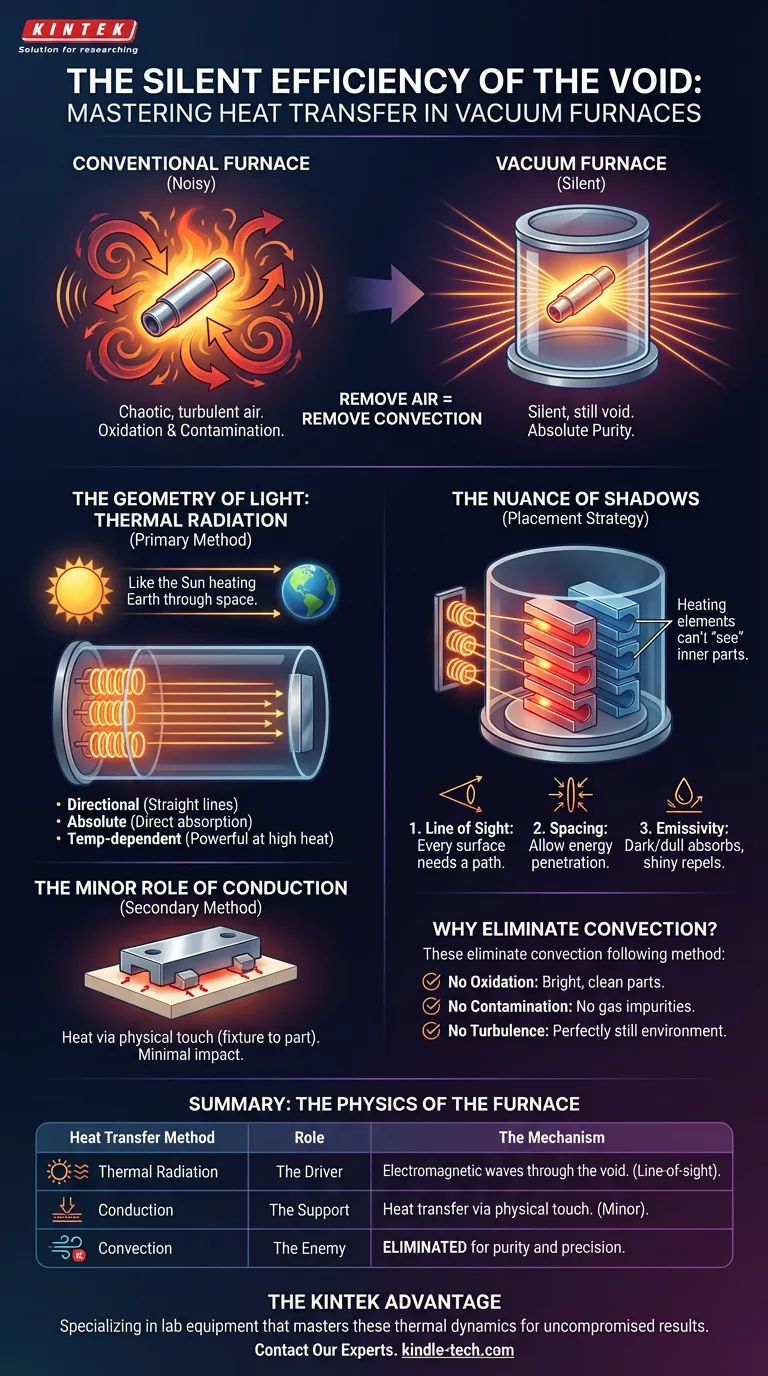

You hear the roar of combustion or the aggressive hum of heavy-duty fans circulating hot air. It is a chaotic, turbulent process. The air is the worker, carrying energy from the heating element to the metal part.

But if you stand next to a vacuum furnace, the experience is unnervingly different. It is silent.

Inside the chamber, there is no air. There is no wind. There is no sound. Yet, inside that void, temperatures are climbing to levels that would melt standard steel in seconds.

This silence represents a fundamental shift in physics. By removing the air, we remove the chaos. But we also remove the primary method of heat transfer we rely on in daily life: convection.

To understand how KINTEK’s equipment achieves such high precision, we have to understand how energy moves through nothingness.

The Problem with Air

In most heating scenarios, air is the medium. You heat the air; the air heats the object.

But for high-precision laboratory work—sintering advanced ceramics, brazing aerospace alloys, or treating medical implants—air is not a helper. It is a contaminant.

At high temperatures, oxygen becomes aggressive. It attacks surfaces, creating oxidation, discoloration, and structural weakness. To achieve perfection, you must eliminate the atmosphere. You must create a vacuum.

But once you remove the air to save the surface, you lose the ability to transfer heat via convection. You are left with the oldest, most primal form of energy transfer in the universe.

The Geometry of Light: Thermal Radiation

How does the sun heat the earth through 93 million miles of empty space? Through thermal radiation.

Vacuum furnaces operate on this exact celestial principle.

Because there is no gas to carry the heat, the system relies on electromagnetic waves (primarily infrared) traveling from the heating elements directly to the workpiece.

This shifts the engineering challenge from fluid dynamics (moving air) to optics (moving light). It creates a scenario defined by "Line of Sight."

The Rules of the Void

When you operate a KINTEK vacuum furnace, you are orchestrating a transfer of light energy. This changes the rules of engagement:

- It is directional: The energy travels in straight lines.

- It is absolute: There is no buffer. The energy hits the part and is absorbed.

- It is temperature-dependent: Radiation is inefficient at low temperatures but becomes exponentially more powerful as heat rises.

The Nuance of Shadows

The reliance on radiation introduces a human element to the process: Placement strategy.

In a convection oven, the moving air swirls around corners and into crevices. It is forgiving. In a vacuum furnace, if a heating element cannot "see" the part, the part does not get heated directly.

This creates "shadows."

If you stack parts too closely, the outer parts will shield the inner ones. The outer parts will overheat while the inner parts remain cool.

To master this process, operators must think like photographers lighting a scene:

- Line of Sight: Every critical surface needs a path to the heater.

- Spacing: Parts must be spaced to allow radiant energy to penetrate the load.

- Emissivity: Dark, dull surfaces absorb this energy greedily. Shiny, reflective surfaces repel it.

The Minor Role of Conduction

There is a secondary player in this silent drama: Conduction.

Because the workpiece must rest on a hearth or a fixture, heat will travel through physical contact. However, in the grand energy balance of a vacuum furnace, this is minimal.

Think of conduction as the anchor that holds the part in place, while radiation does the heavy lifting of transformation.

Why We Eliminate Convection

Why go through the trouble of managing shadows and emissivity? Why not just keep the air?

Because the trade-off is purity.

By eliminating convection, we eliminate the variables that ruin experiments and production runs.

- No Oxidation: Parts emerge bright and clean.

- No Contamination: There is no gas to transport dust or impurities.

- No Turbulence: The environment is perfectly still.

Summary: The Physics of the Furnace

Here is how the energy transfer mechanisms stack up in a vacuum environment:

| Heat Transfer Method | Role | The Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Radiation | The Driver | Electromagnetic waves travel through the void. Requires line-of-sight. |

| Conduction | The Support | Heat transfer via physical touch (fixture to part). Minor impact. |

| Convection | The Enemy | Intentionally eliminated to prevent oxidation and ensure surface purity. |

The KINTEK Advantage

Engineering is about choosing your constraints.

In a vacuum furnace, we choose the constraint of radiation (requiring careful placement) to gain the advantage of absolute purity.

For laboratories requiring uncompromised results, understanding this physics is the first step. The second step is choosing equipment designed to optimize it.

KINTEK specializes in laboratory equipment that masters these thermal dynamics. Our vacuum furnaces are engineered to maximize radiative efficiency, ensuring that your research is defined by precision, not contamination.

Contact Our Experts to discuss how KINTEK can bring the precision of the void to your laboratory.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Brazing Furnace

- Laboratory Vacuum Tilt Rotary Tube Furnace Rotating Tube Furnace

- 1200℃ Controlled Atmosphere Furnace Nitrogen Inert Atmosphere Furnace

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

Related Articles

- Beyond Heat: Mastering Material Purity in the Controlled Void of a Vacuum Furnace

- Your Furnace Hit the Right Temperature. So Why Are Your Parts Failing?

- The Architecture of Emptiness: Achieving Metallurgical Perfection in a Vacuum

- The Engineering of Nothingness: Why Vacuum Furnaces Define Material Integrity

- Why Your High-Temperature Processes Fail: The Hidden Enemy in Your Vacuum Furnace