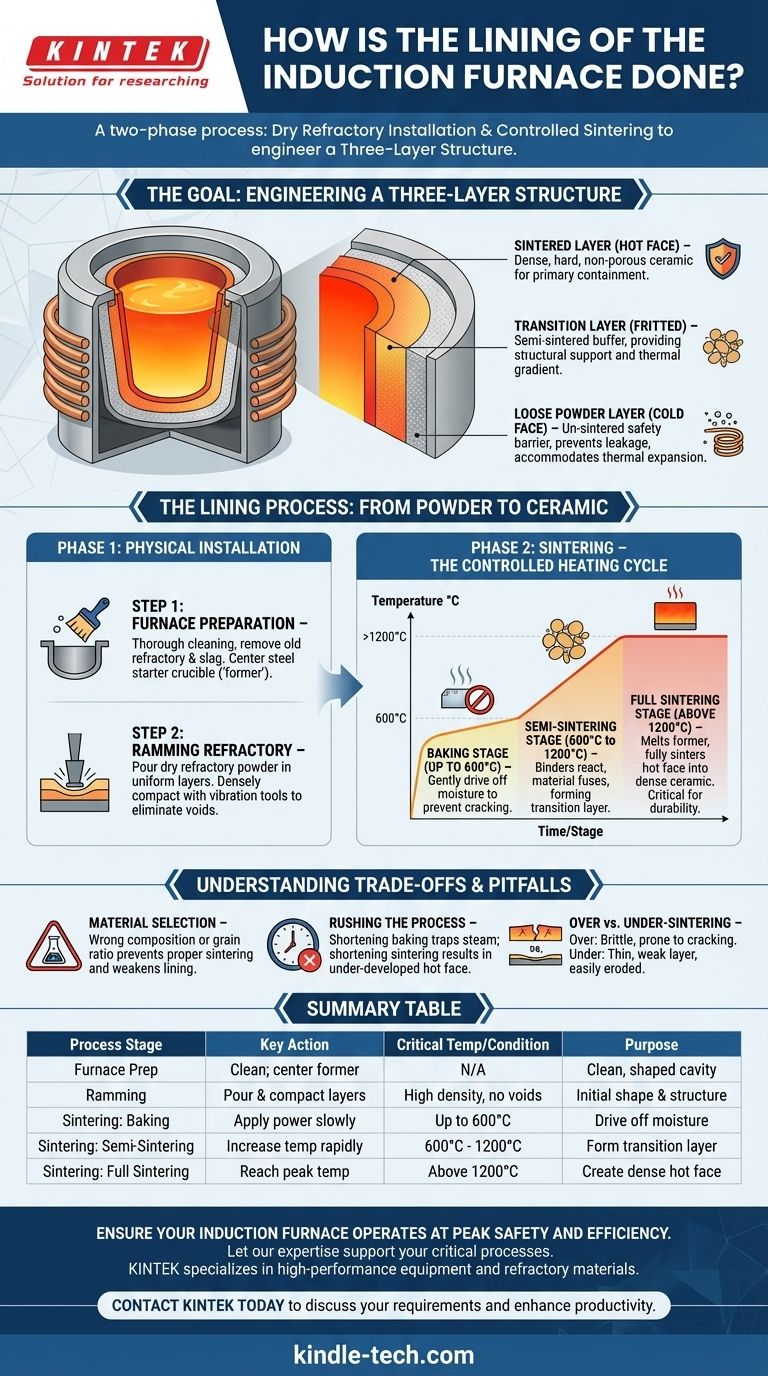

Lining an induction furnace is a two-phase process that involves the careful installation of a dry refractory material, followed by a highly controlled heating process known as sintering. This procedure transforms the loose powder into a solid, multi-layered ceramic crucible capable of containing molten metal at extreme temperatures.

The ultimate goal of furnace lining is not merely to fill a gap, but to engineer a specific three-layer structure within the refractory material. Success depends entirely on a disciplined, step-by-step approach to both the physical installation and the subsequent heating cycle.

The Goal: Engineering a Three-Layer Structure

A properly sintered lining is not a uniform block. It is designed to have three distinct zones, each serving a critical function for safety and longevity.

The Sintered Layer (Hot Face)

This is the innermost layer, in direct contact with the molten metal. It is heated to the point of becoming a dense, hard, and non-porous ceramic. This layer provides the primary containment for the melt.

The Transition Layer (Fritted)

Behind the hot face is a semi-sintered zone. The refractory grains have fused but have not formed a fully dense ceramic. This layer acts as a crucial buffer, providing structural support and a thermal gradient.

The Loose Powder Layer (Cold Face)

The outermost layer, nearest the induction coil, remains as un-sintered powder. This loose material acts as the final safety barrier, preventing any potential metal leakage from reaching the coils. It also accommodates thermal expansion and contraction of the furnace.

The Lining Process: From Powder to Ceramic

Achieving the three-layer structure requires a meticulous, multi-stage process. It begins with the physical installation of the refractory material and concludes with the critical sintering cycle.

Step 1: Furnace Preparation

Before any new material is added, the furnace must be thoroughly cleaned of all old refractory and slag. A steel starter crucible, or "former," is then centered within the furnace coil. This former will hold the shape of the lining and will be melted out during the first heat.

Step 2: Ramming the Refractory Material

The dry refractory powder, typically a silica-based material for ferrous metals, is poured in uniform layers between the furnace wall and the steel former. Each layer is densely compacted using specialized pneumatic or electric vibration tools to ensure high density and eliminate voids.

Step-3: Sintering - The Controlled Heating Cycle

This is the most critical phase, where heat transforms the rammed powder. It follows a precise temperature schedule.

-

Baking Stage (Up to 600°C): Power is applied slowly to gradually heat the lining. This stage is held to gently drive off any atmospheric moisture trapped in the material. Heating too quickly here can create steam, leading to cracks.

-

Semi-Sintering Stage (600°C to 1200°C): The temperature is increased more rapidly. In this range, the binder agents in the refractory mix begin to react, and the material starts to fuse and harden, forming the transition layer.

-

Full Sintering Stage (Above 1200°C): The furnace is brought to its maximum operating temperature. The steel former melts, and this first heat fully sinters the hot face, creating the dense ceramic layer. The duration and peak temperature at this stage determine the thickness and durability of the crucial sintered layer.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Pitfalls

The success of a lining is highly sensitive to process variables. Missteps can lead to drastically reduced service life or catastrophic failure.

The Impact of Material Selection

The chemical composition and particle size distribution of the refractory material are not optional details. Using the wrong material for your application (e.g., silica for a non-ferrous melt) or a product with an incorrect grain ratio will prevent proper compaction and sintering, leading to a weak lining.

The Danger of Rushing the Process

The temptation to shorten the heating cycle to save time is a common and costly mistake. Rushing the initial baking stage traps steam, causing spalling and structural weakness. Shortening the final sintering stage results in an under-developed hot face that will erode quickly.

Over-Sintering vs. Under-Sintering

The final sintering temperature and time directly influence the thickness of the hard, sintered layer.

- Under-sintering creates a thin, weak layer that is easily eroded by the molten metal.

- Over-sintering creates an excessively thick and brittle layer that is prone to deep cracking during thermal cycles.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The lining process must be executed with your primary operational goal in mind.

- If your primary focus is safety and longevity: Adhere strictly to the sintering schedule to develop the ideal three-layer structure, ensuring a robust hot face and a protective loose-powder backup layer.

- If your primary focus is melt quality: Ensure the furnace is perfectly clean before installation and use only fresh, uncontaminated refractory material to prevent impurities from entering the melt.

- If your primary focus is operational efficiency: Follow the manufacturer's documented procedure without deviation. Shortcuts in ramming or sintering will invariably lead to premature failure and costly downtime.

Ultimately, the furnace lining is the heart of your melt deck's reliability, and its integrity is a direct result of process discipline.

Summary Table:

| Process Stage | Key Action | Critical Temperature/Condition | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Furnace Preparation | Clean old refractory; center steel former | N/A | Create a clean, shaped cavity for new lining |

| Ramming | Pour and compact dry refractory in layers | High density, no voids | Form the initial shape and ensure structural integrity |

| Sintering: Baking | Apply power slowly; hold temperature | Up to 600°C | Gently drive off moisture to prevent cracking |

| Sintering: Semi-Sintering | Increase temperature more rapidly | 600°C to 1200°C | Fuse grains to form the critical transition/buffer layer |

| Sintering: Full Sintering | Reach peak operating temperature; melt steel former | Above 1200°C | Create the dense, hard sintered layer (hot face) |

Ensure your induction furnace operates at peak safety and efficiency. The integrity of your furnace lining is paramount to melt quality, equipment longevity, and operator safety. KINTEK specializes in high-performance lab equipment and consumables, including the refractory materials and expert guidance needed for a perfect lining installation.

Let our expertise support your critical processes. Contact KINTEK today to discuss your specific furnace requirements and how our solutions can enhance your laboratory's productivity and reliability.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Furnace for Heat Treat and Sintering

- 1700℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- Vacuum Sealed Continuous Working Rotary Tube Furnace Rotating Tube Furnace

- High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory Debinding and Pre Sintering

- Evaporation Crucible for Organic Matter

People Also Ask

- Why is it necessary to maintain a high-vacuum environment within a vacuum hot press furnace? Optimize Cu-SiC Sintering

- Why is the vacuum system of a Vacuum Hot Pressing furnace critical for ODS ferritic stainless steel performance?

- How does a vacuum hot press furnace achieve the densification of ZrB2–SiC–TaC? Unlock Ultra-High Ceramic Density

- How does a vacuum hot press (VHP) contribute to the densification of Al-Cu-ZrC composite materials? Key VHP Benefits

- What role does a vacuum hot pressing sintering furnace play in the fabrication of CuCrFeMnNi alloys? Achieve High Purity