The Enemy You Can't See

In materials science, failure almost always begins in the same place: the empty spaces.

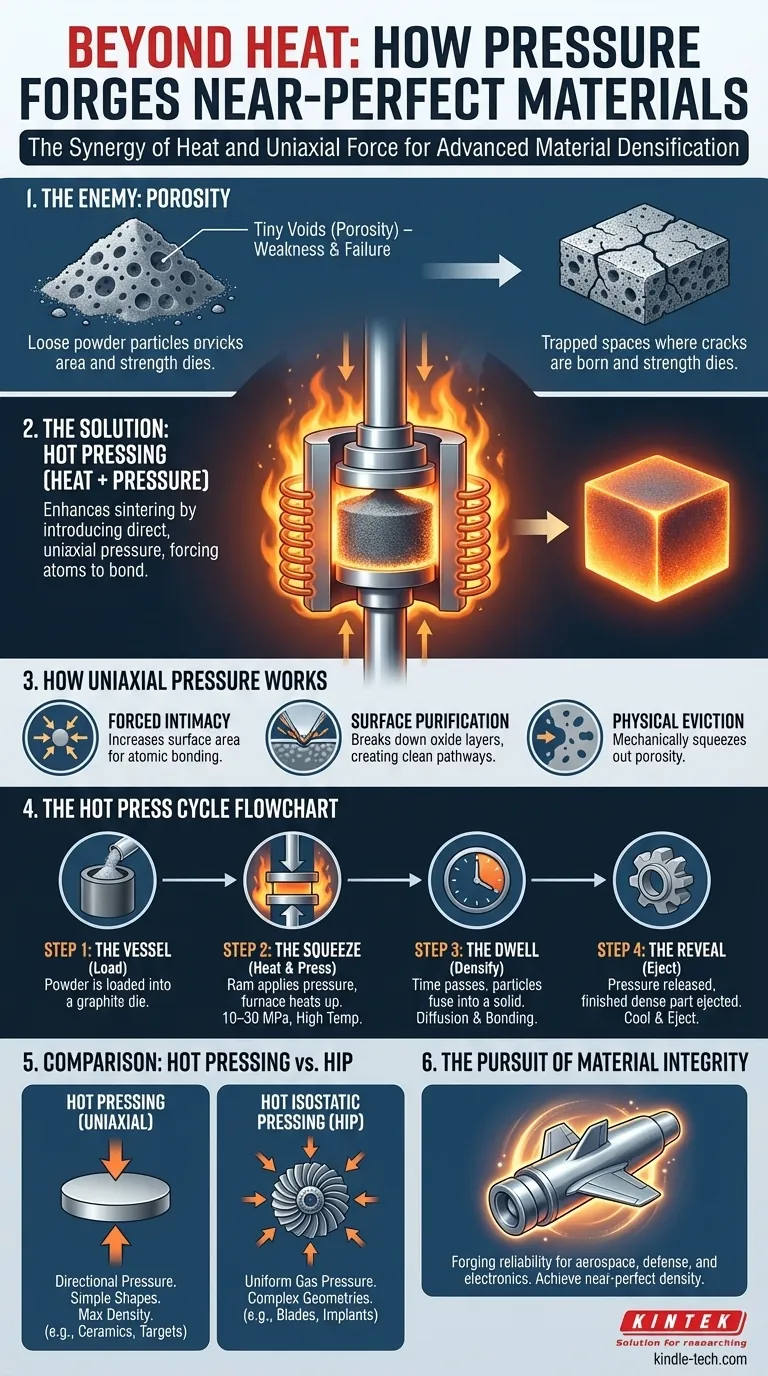

Porosity—the tiny, microscopic voids trapped between particles—is the invisible enemy. It's where cracks are born and where mechanical strength dies. For decades, engineers have fought this emptiness with heat, using a process called sintering to coax powdered materials into a solid, unified whole.

Sintering works by making atoms mobile. At high temperatures, they migrate across particle boundaries, slowly closing the gaps. But the process is patient, often slow, and rarely perfect. Some voids inevitably get trapped.

To create the next generation of advanced ceramics, composites, and alloys, we can't just ask atoms to bond. We have to force them.

The Elegant Solution: Adding Force to the Fire

This is the core principle of hot pressing. It's a process that enhances sintering by introducing a second, powerful variable: direct, uniaxial pressure.

While heat makes the material pliable and encourages atomic diffusion, the constant, controlled pressure physically compacts the powder. It's a simple, almost brute-force addition, but its effects are profound.

How Uniaxial Pressure Changes Everything

The synergy between heat and pressure accelerates densification in three critical ways:

- Forced Intimacy: Pressure shoves powder particles into intimate contact, dramatically increasing the surface area where atomic bonding can occur.

- Surface Purification: The grinding force breaks down stubborn surface oxides that can inhibit bonding, creating cleaner pathways for diffusion.

- Physical Eviction: Most importantly, the pressure mechanically squeezes out the voids, systematically eliminating the porosity that heat alone might leave behind.

The result is a material that achieves a density remarkably close to its theoretical maximum. The process is often faster and can be accomplished at lower temperatures than conventional sintering, preserving the material's fine-grained microstructure.

The Anatomy of a Hot Press Cycle

While the physics are complex, the workflow is a model of engineering precision. It's a controlled sequence designed to transform loose powder into a monolithic solid.

-

Step 1: The Vessel The powder is loaded into a simple-shaped die, which is very often machined from graphite. Graphite is the material of choice for its incredible temperature resistance, excellent thermal conductivity, and machinability.

-

Step 2: The Squeeze The die is placed within the hot press. An induction furnace or resistive heaters bring the temperature up, while a hydraulic ram applies constant, uniaxial pressure, typically in the range of 10–30 MPa.

-

Step 3: The Dwell The system holds the material at a target temperature and pressure for a specific duration. This "dwell time" is where the densification occurs, as the particles deform, diffuse, and bond into a solid mass.

-

Step 4: The Reveal After densification is complete, the component is cooled under controlled conditions, the pressure is released, and the finished, high-density part is ejected.

The Engineer's Dilemma: Choosing the Right Pressure

"Hot press" is a term that requires context. Understanding its key distinctions is crucial for selecting the right manufacturing path—a decision that balances performance, geometry, and cost.

Hot Pressing vs. Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP)

The fundamental difference lies in how pressure is applied. Think of hot pressing as a precise hammer (uniaxial force), while HIP is like shrink-wrapping (isostatic, gas-based force from all directions).

| Feature | Hot Pressing (Uniaxial) | Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure Type | Directional (e.g., top and bottom) | Uniform (from all directions) |

| Geometry | Simple shapes (discs, plates, cylinders) | Complex, near-net shapes |

| Core Advantage | Maximum density in basic forms | Densification of intricate geometries |

| Best For | Advanced ceramics, sputtering targets | Turbine blades, medical implants |

If your goal is absolute maximum density in a simple geometry, hot pressing is an incredibly powerful and efficient choice. If your part has complex curves and internal features, HIP is the superior technology.

When Simpler Is Better

For high-volume production of less critical components, a traditional "press-and-sinter" approach—where powder is compacted at room temperature first, then heated separately—often provides the most economical path. The choice always comes back to the demands of the final application.

The Pursuit of Material Integrity

Ultimately, the fight against porosity is a fight for reliability. In aerospace, defense, and high-performance electronics, you cannot afford the weakness that comes from empty space. Hot pressing provides a direct and powerful method for forging materials with near-perfect density.

Achieving this level of material integrity requires not just knowledge, but equipment capable of precise and repeatable control over temperature and pressure. Equipping your lab for this level of material perfection is the first step toward innovation. Contact Our Experts to explore the right solutions for your goals.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine Heated Vacuum Press

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Heated Vacuum Press Machine Tube Furnace

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine for Lamination and Heating

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Furnace for Heat Treat and Sintering

- Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Vacuum Box Laboratory Hot Press

Related Articles

- Comprehensive Guide to Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Application

- The Physics of Perfection: Why a Vacuum Is the Material Scientist's Most Powerful Tool

- The Physics of Permanence: How Hot Presses Forge the Modern World

- Beyond Heat: Why Pressure is the Deciding Factor in Advanced Materials

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace: A Comprehensive Guide