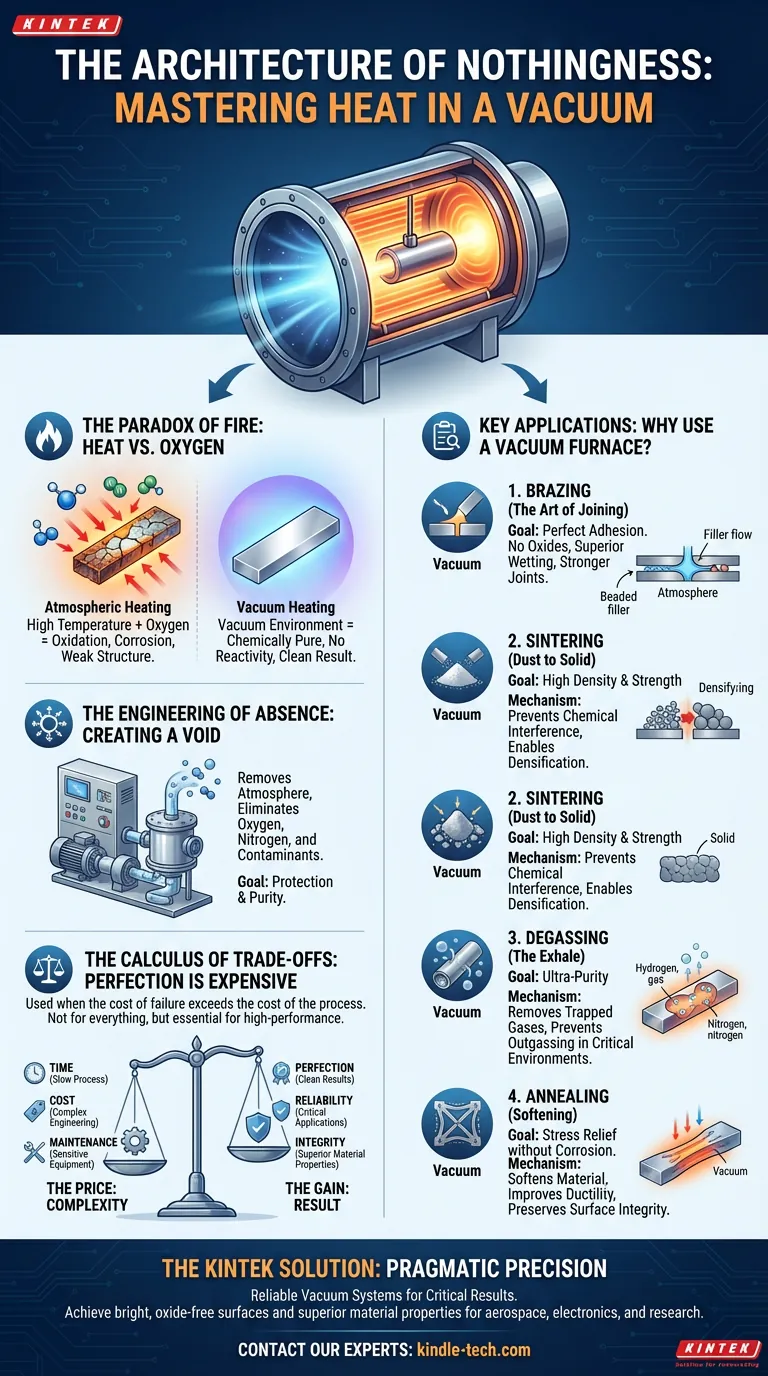

The Paradox of Fire

Heat is the oldest tool in engineering. It hardens, it softens, and it fuses.

But heat has a jealous partner: Oxygen.

At room temperature, oxygen is benign. But as you raise the temperature to the levels required for metallurgy—1,000°C or more—the air around us becomes an aggressor. It attacks metal surfaces. It creates oxides. It compromises structure.

This is the central problem of high-end manufacturing. You need the heat to transform the material, but the atmosphere ruins it in the process.

This is where the vacuum furnace enters the story. It is not just a machine for getting things hot. It is a machine for creating a void.

The Engineering of Absence

A vacuum furnace is a specialized vessel designed to solve one specific problem: Chemical Reactivity.

When aerospace engineers work with titanium, or electronics manufacturers work with semiconductors, they are dealing with materials that are highly reactive. If you heat titanium in a normal oven, it doesn't just get hot; it reacts with nitrogen and oxygen to become brittle. It effectively ruins itself.

The vacuum furnace removes the variable. By pumping out the atmosphere, we create a chemically pure environment.

The goal isn't just temperature. The goal is protection.

1. The Art of Brazing

Brazing is the act of joining two metals by flowing a filler metal between them.

In a standard atmosphere, this is a messy fight. Oxides form on the surface of the metals, acting like a barrier. The filler metal beads up. The joint fails.

In a vacuum, the story changes.

- There is no oxygen to form a barrier.

- The filler metal flows perfectly, wetting the surface.

- The result is a joint that is often stronger than the base materials themselves.

For aerospace turbines or medical devices, where a failed joint means catastrophe, this "cleanliness" is not a luxury. It is a requirement.

2. Sintering: From Dust to Solid

Sintering is the process of taking powdered material—metal or ceramic—and fusing it into a solid mass without melting it completely.

Imagine trying to glue dust together while the dust is actively trying to rust. That is atmospheric sintering.

Vacuum sintering changes the physics. By removing air, we prevent chemical compounds from forming between the particles. The material densifies. It becomes stronger. It results in a product with superior structural integrity, essential for advanced ceramics and hard metals.

3. Degassing: The Exhale

Materials breathe. During their creation, metals often trap gases like hydrogen or nitrogen deep within their lattice structure.

If you take that metal and put it into a high-vacuum environment later (like an X-ray tube or a particle accelerator), those trapped gases will seep out. This "outgassing" can ruin sensitive electronics.

A vacuum furnace acts as a cleansing lung. By heating the material in a vacuum, we force it to release these trapped gases before the part is finalized. It is a purification ritual for high-performance matter.

The Calculus of Trade-offs

If vacuum furnaces are so superior, why don't we use them for everything?

Because perfection is expensive.

Morgan Housel often writes about how everything has a price, and the price is not always on the price tag. The price of a vacuum furnace is complexity.

- Time: They are slow. You cannot simply open the door. You must pump the chamber down to a void, heat it, and then carefully cool it.

- Cost: The pumps, seals, and containment vessels required to hold a vacuum against the crushing weight of the atmosphere are costly engineering feats.

- Maintenance: A leak the size of a human hair can ruin a batch.

You do not use a vacuum furnace to bake a brick. You use it when the cost of failure exceeds the cost of the process.

Summary of Applications

Here is the breakdown of when the void is necessary:

| Application | The Goal | The mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Brazing | Perfect adhesion | Removes oxides that block filler flow. |

| Sintering | High density | Prevents chemical interference between particles. |

| Annealing | Softening | Relieves stress without surface corrosion. |

| Degassing | Purity | Removes internal trapped gases. |

The KINTEK Solution

There is a romance to the vacuum furnace. It is the only place on Earth where we can manipulate matter without the interference of nature.

However, the equipment itself must be pragmatic. It must be reliable.

At KINTEK, we understand that you aren't buying a furnace because you want a machine; you are buying it because you need a result. You need a bright, oxide-free surface. You need a brazed joint that will hold up at 30,000 feet.

Whether you are sintering advanced ceramics or degassing components for electron microscopy, the equipment must disappear into the background, leaving only the perfect result.

Contact Our Experts to discuss how our vacuum systems can bring architectural precision to your laboratory processes.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Brazing Furnace

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Molybdenum Wire Sintering Furnace for Vacuum Sintering

Related Articles

- The Engineering of Nothingness: Why Vacuum Furnaces Define Material Integrity

- The Architecture of Emptiness: Achieving Metallurgical Perfection in a Vacuum

- Your Vacuum Furnace Hits the Right Temperature, But Your Process Still Fails. Here’s Why.

- Vacuum Induction Furnace Fault Inspection: Essential Procedures and Solutions

- Materials Science with the Lab Vacuum Furnace