A laboratory hydraulic press is the fundamental tool used to overcome the physical limitations of solid materials in battery assembly. It applies immense mechanical force—ranging from roughly 55 MPa to over 500 MPa—to compress loose electrolyte powders into cohesive, dense layers. This compression is the primary mechanism used to eliminate air voids and force solid particles into the intimate physical contact required for ionic conduction.

Core Takeaway In the absence of liquid electrolytes that naturally "wet" surfaces, a hydraulic press acts as the enabler of ion transport. By densifying loose powder into a solid pellet (often achieving 85% to 99% relative density), the press minimizes grain boundary impedance and creates the continuous pathways necessary for lithium ions to move, while simultaneously creating a structure strong enough to block dendrites.

The Physics of Densification

The transition from loose powder to a functional solid-state battery component relies entirely on the reduction of void space. The hydraulic press facilitates this through three specific mechanisms.

Minimizing Grain Boundary Impedance

In a solid-state battery, ions cannot travel through air gaps. They require a continuous solid path.

The primary function of the hydraulic press is to reduce grain boundary impedance. By applying high pressure (e.g., 100 MPa for materials like Li3YCl6), the press forces individual powder particles to deform and bond. This establishes continuous lithium-ion transport channels that would otherwise be interrupted by microscopic voids.

Replicating the "Wetting" Effect

Liquid electrolytes naturally penetrate porous electrodes, ensuring contact. Solid electrolytes are rigid and lack this ability.

The hydraulic press substitutes chemical "wetting" with mechanical forcing. High-pressure cold pressing drives the solid electrolyte particles into the surface irregularities of the cathode and anode. This physical interlocking is the only way to lower interfacial impedance to a level where the battery can function efficiently.

Achieving Structural Integrity

Loose electrolyte powder has no mechanical strength.

The press compacts this powder into a "green pellet" or a bilayer structure. For example, compressing Li3YCl6 to approximately 85% relative density provides the mechanical robustness needed to support the cathode layer. Without this structural support, the battery layers would delaminate or crumble during handling and operation.

Performance and Safety Implications

Beyond basic conductivity, the density achieved by the hydraulic press plays a critical role in the safety and longevity of the cell.

Suppressing Lithium Dendrites

Lithium dendrites are needle-like growths that can pierce electrolytes and cause short circuits.

High-pressure densification is a key defense mechanism. When pressures approaching 500 MPa are used, the relative density of the electrolyte pellet can reach approximately 99%. This elimination of pores creates a physical barrier that is dense enough to block the penetration of lithium dendrites, significantly reducing the risk of short circuits.

Managing Volume Changes

Battery materials expand and contract during charge and discharge cycles.

If the initial contact is weak, these volume changes will cause the components to separate, breaking the ionic pathway. The high pressure (e.g., 380 MPa to 480 MPa) applied during assembly creates a tight solid-solid contact interface. This initial compression helps the components resist contact separation, ensuring the battery maintains performance over repeated cycles.

Critical Considerations for Pressure Application

While high pressure is essential, it must be applied with precision based on the specific material chemistry.

Matching Pressure to Material Goals

There is no single "correct" pressure; it is material-dependent.

- Moderate Pressure (approx. 100 MPa): Often sufficient for halide electrolytes (like Li3YCl6) to achieve ~85% density and adequate conductivity.

- High Pressure (380–500 MPa): typically required for sulfide electrolytes or when the goal is near-perfect density (99%) to maximize dendrite suppression.

The Density vs. Performance Balance

Achieving 100% density is difficult and requires immense force. However, data suggests that even 85% density is often sufficient to establish effective transport channels. The goal of the hydraulic press is not just "maximum pressure," but reaching the specific density threshold where grain boundary resistance drops and mechanical stability is secured.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The specific pressure parameters you set on your hydraulic press should be dictated by the primary failure mode you are trying to prevent.

- If your primary focus is Ion Transport Efficiency: Target pressures (around 100 MPa for halides) that achieve at least 85% density to minimize grain boundary impedance and establish continuous channels.

- If your primary focus is Safety and Dendrite Resistance: Utilize higher pressures (up to 500 MPa) to maximize relative density to ~99%, effectively eliminating the pores that allow dendrite penetration.

- If your primary focus is Cycle Life Stability: Ensure sufficient cold-pressing pressure (380+ MPa) to lock the cathode and electrolyte into a tight interface that can withstand volume expansion without delaminating.

The hydraulic press is not merely a shaping tool; it is the critical processing step that transforms electrically isolated powders into a cohesive, conductive, and safe electrochemical system.

Summary Table:

| Feature | Pressure Range | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Ion Transport | ~100 MPa | Reduces grain boundary impedance; achieves ~85% density |

| Interfacial Contact | 380 - 480 MPa | Replicates 'wetting' effect; resists volume change separation |

| Dendrite Safety | Up to 500+ MPa | Maximizes relative density to ~99%; blocks short circuits |

| Structural Integrity | Material Dependent | Prevents delamination; creates robust 'green pellets' |

Elevate Your Battery Research with KINTEK Precision

Unlock the full potential of your all-solid-state battery research with KINTEK’s industry-leading laboratory hydraulic presses. Whether you are working on halide or sulfide electrolytes, our comprehensive range of manual, electric, and isostatic presses provides the precise pressure control (up to 500 MPa and beyond) required for 99% densification and dendrite suppression.

Beyond pellet pressing, KINTEK specializes in high-performance laboratory equipment including high-temperature furnaces, crushing and milling systems, and specialized battery research tools. Partner with us to ensure superior ionic conduction and structural integrity in every cell you build.

Ready to optimize your densification process? Contact a KINTEK expert today to find the perfect pressing solution for your lab!

Related Products

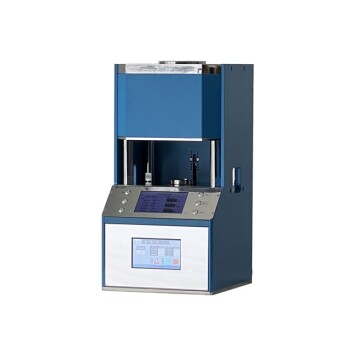

- Manual High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

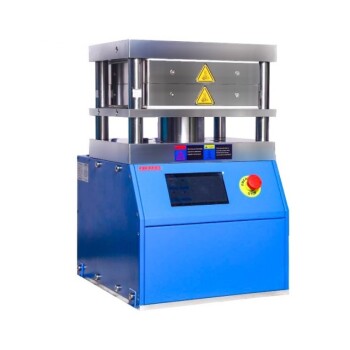

- Automatic High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

- Laboratory Manual Hydraulic Pellet Press for Lab Use

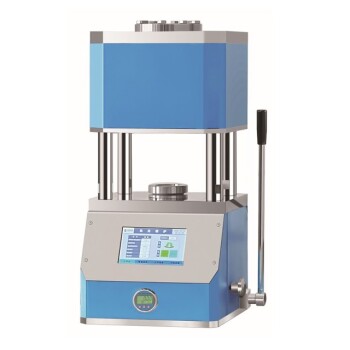

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Split Electric Lab Pellet Press

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Laboratory Hot Press 25T 30T 50T

People Also Ask

- Why do you need to follow the safety procedure in using hydraulic tools? Prevent Catastrophic Failure and Injury

- Does a hydraulic press have heat? How Heated Platens Unlock Advanced Molding and Curing

- What technical conditions does a heated hydraulic press provide for PEO batteries? Optimize Solid-State Interfaces

- What does a hydraulic heat press do? Achieve Industrial-Scale, Consistent Pressure for High-Volume Production

- What is a hot hydraulic press? Harness Heat and Pressure for Advanced Manufacturing