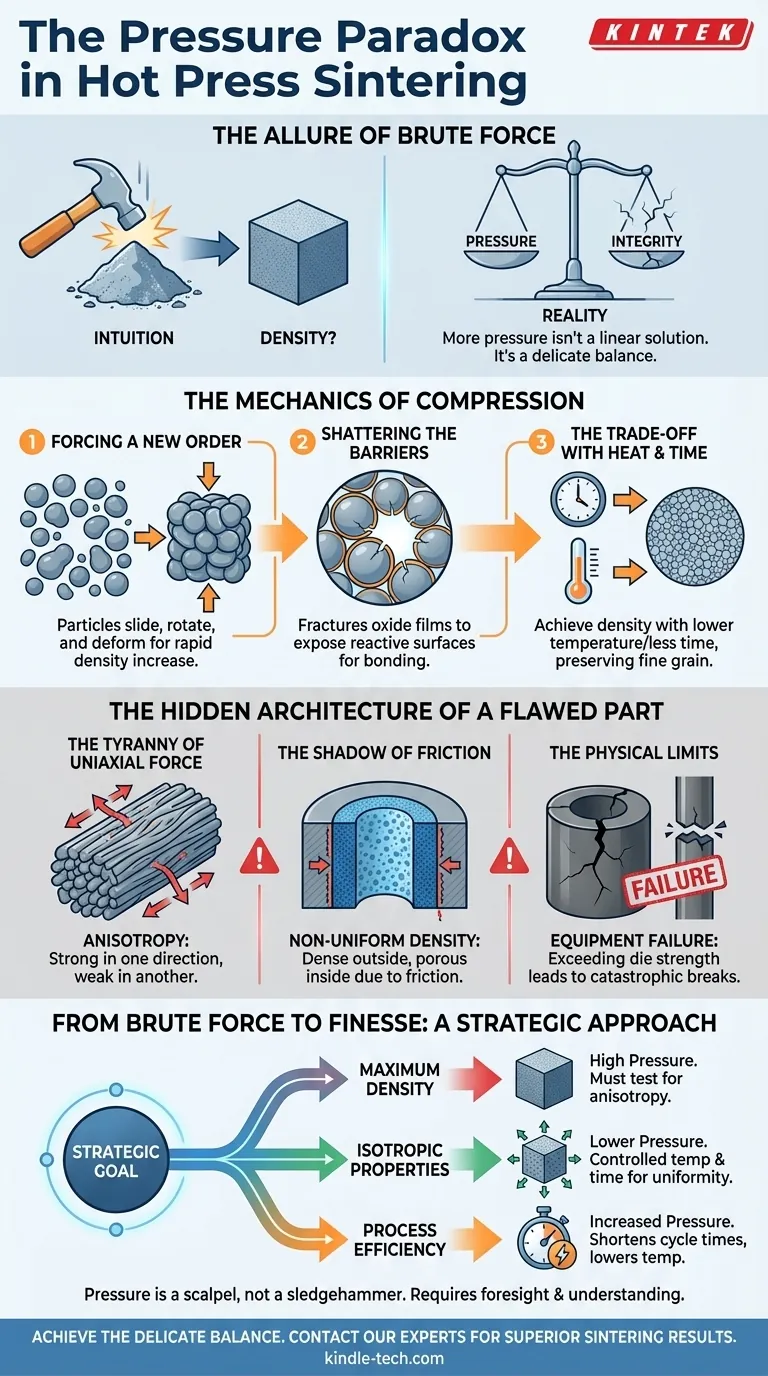

The Allure of Brute Force

When faced with a challenge of consolidation, the human instinct is simple: apply more force. If you want to pack something tighter, you squeeze it harder. This intuition serves us well in daily life, but in the precise world of materials science, it’s both a powerful tool and a dangerous trap.

In hot press sintering, pressure is the primary lever we pull to transform loose powder into a dense, solid component. It feels like a linear solution—more pressure should yield a better part. The reality, however, is a delicate paradox. Pressure accelerates the journey to density, but it can quietly introduce deep, structural flaws that compromise the final product's integrity.

Mastering this process is not about maximizing force; it's about understanding its complex consequences.

The Mechanics of Compression: What Pressure Actually Does

Applying immense pressure to a powder compact isn't just crude squeezing. It's a targeted intervention that fundamentally alters the physics of consolidation at a microscopic level.

Forcing a New Order

At the start of the cycle, the powder is a disordered collection of particles and voids. Increased pressure acts as an overwhelming force, causing particles to slide, rotate, and rearrange themselves into a more tightly packed structure. As the force continues, it induces plastic deformation, literally changing the shape of the particles to eliminate the remaining gaps. This is the brute-force benefit: a rapid and dramatic increase in density.

Shattering the Barriers

Nearly every powder particle is cloaked in a microscopically thin, passive oxide film. This layer is an enemy of a strong bond. High pressure creates immense stress at the contact points between particles, physically fracturing these brittle shells. This act of destruction is crucial, as it exposes fresh, highly reactive surfaces that can form powerful metallurgical or ceramic bonds, creating a truly monolithic part.

The Trade-Off with Heat and Time

Pressure, temperature, and time are inextricably linked. By increasing the pressure, you can often achieve your target density at a lower temperature or in less time. This is more than just an efficiency gain. Lower temperatures can prevent undesirable grain growth, preserving the fine-grained microstructure that often imparts superior strength and toughness to the final material.

The Hidden Architecture of a Flawed Part

The most dangerous problems in engineering are the ones you can't see. While excessive pressure delivers density, it can build a flawed architecture into the very core of your component.

The Tyranny of Uniaxial Force

Hot pressing is typically a one-dimensional action—force is applied from a single direction. This can persuade non-spherical particles to align themselves like fallen dominoes, perpendicular to the pressing direction.

The result is anisotropy. The material develops a "grain," much like wood. It may be incredibly strong when tested along one axis but surprisingly weak along another. This hidden characteristic can lead to unexpected and catastrophic failure in real-world applications.

The Shadow of Friction

Pressure is not transmitted perfectly through a powder mass. As the press ram moves, friction between the powder and the die walls creates a pressure gradient. The force is strongest near the ram and weakest deep inside the component's core.

This can create a part that is dense on the outside but porous on the inside—a dangerous illusion of structural integrity. This non-uniform density is a common but often overlooked defect.

The Physical Limits of Your Tools

Finally, there is the simple, unforgiving reality of physics. Your press has a maximum force rating, and more critically, your graphite die has a finite compressive strength. The temptation to push the limits can be high, but exceeding them results in catastrophic mold failure—a costly and time-consuming setback.

From Brute Force to Finesse: A Strategic Approach

The optimal pressure is not a universal constant but a strategic choice dictated by your ultimate goal. The question is not "How much pressure can I apply?" but "What am I trying to achieve?"

-

For Maximum Density: If achieving the highest possible theoretical density is the sole priority, use the highest pressure your equipment and die can safely sustain. However, you must be prepared to rigorously test for and mitigate the resulting anisotropy.

-

For Isotropic Properties: If uniformity in all directions is non-negotiable, a more patient approach is required. Favor a lower pressure combined with meticulously controlled temperature and time to allow for more uniform densification.

-

For Process Efficiency: If throughput and energy savings are the primary drivers, increasing pressure is a highly effective way to shorten cycle times and reduce the required sintering temperature.

Pressure should be treated as a scalpel, not a sledgehammer. It is a precise tool for manipulating material consolidation, and its successful application requires foresight and a deep understanding of the trade-offs.

Achieving this delicate balance of force, heat, and time requires equipment that is both powerful and precise. Having a reliable hot press and high-quality consumables ensures that the parameters you set are the conditions your material actually experiences, allowing you to move from theory to a flawless finished component. If you are looking to refine your sintering process for superior results, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

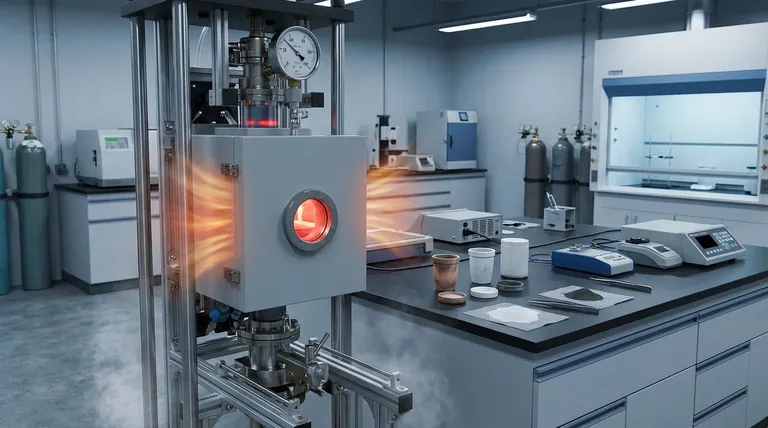

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Heated Vacuum Press Machine Tube Furnace

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine Heated Vacuum Press

- Manual High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

- Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Vacuum Box Laboratory Hot Press

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Furnace for Heat Treat and Sintering

Related Articles

- Molybdenum Vacuum Furnace: High-Temperature Sintering and Heat Treatment

- From Dust to Density: The Microstructural Science of Hot Pressing

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace: A Comprehensive Guide

- Beyond Heat: How Pressure Forges Near-Perfect Materials

- Comprehensive Guide to Spark Plasma Sintering Furnaces: Applications, Features, and Benefits