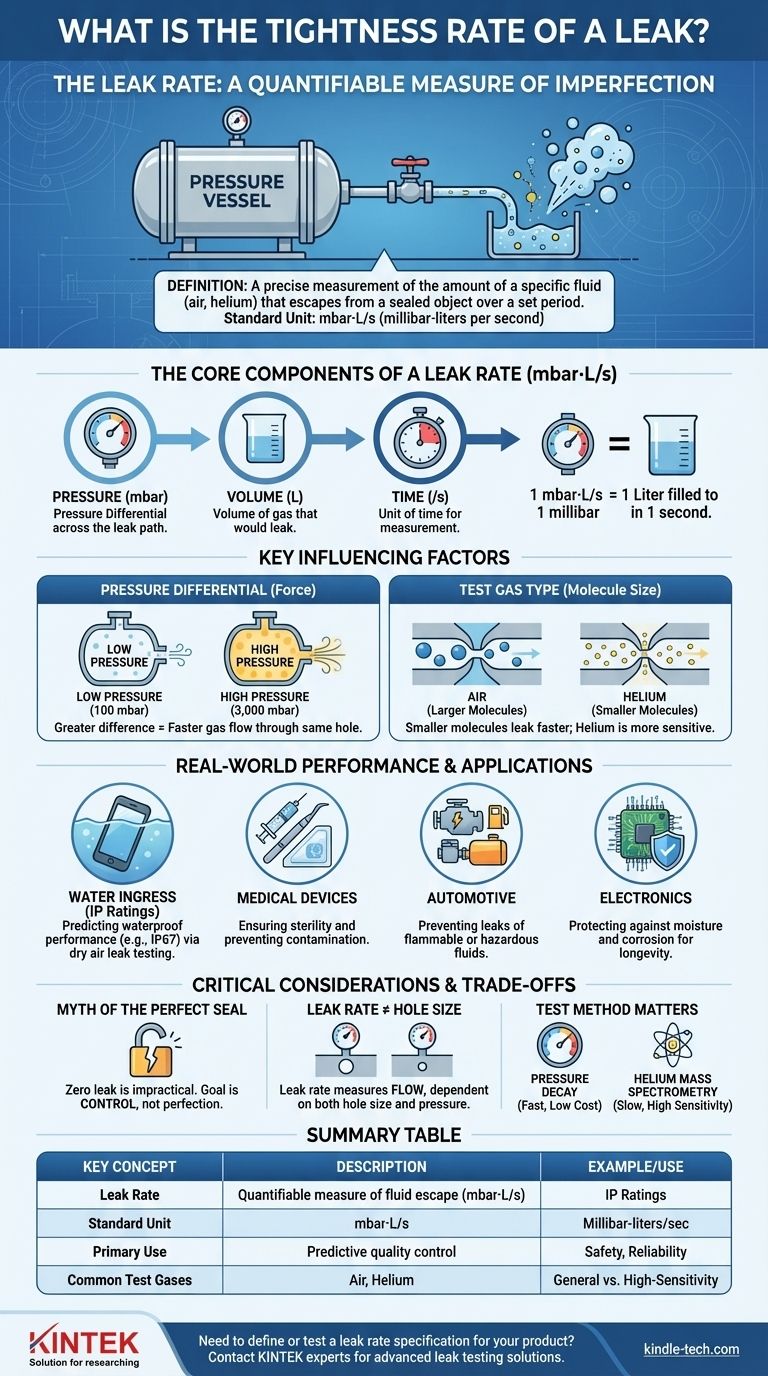

The tightness rate of a leak, more commonly known as the leak rate, is a precise measurement of the amount of a specific fluid (like air or helium) that escapes from a sealed object over a set period. It is not just a simple "yes" or "no" for a leak, but a quantifiable value that defines how "leak-proof" a component actually is. The standard unit for this is pressure-volume per time, such as millibar-liters per second (mbar·L/s).

A leak rate is the critical engineering metric used to move from the abstract idea of a "perfect seal" to a measurable, acceptable level of imperfection. It quantifies how much a product leaks under specific conditions, allowing manufacturers to ensure it meets safety, reliability, and performance standards like waterproof ratings.

The Core Components of a Leak Rate

To truly understand a leak rate specification, you must understand the three variables that define it. The rate is a function of the pressure difference, the type of gas, and the physical pathway of the leak.

The Unit of Measurement (mbar·L/s)

The standard unit, mbar·L/s, can seem abstract, but it represents a physical reality.

- mbar (millibar): This is the pressure differential across the leak path. A leak only occurs when there's a pressure difference between the inside and outside of a part.

- L (liters): This is the volume of gas that would leak out.

- /s (per second): This is the unit of time over which the leak is measured.

A leak rate of 1 mbar·L/s means that in one second, enough gas leaks out to fill a one-liter volume to a pressure of one millibar.

The Role of Pressure Differential

A leak is passive. Gas doesn't decide to escape; it's pushed. The greater the pressure difference between the inside and outside of a component, the faster the gas will flow through a given hole.

This means a single physical flaw can have many different leak rates. A tiny crack might have a low leak rate at 100 mbar of pressure but a very high leak rate at 3,000 mbar of pressure.

The Test Gas (Air vs. Helium)

The type of gas used for testing is critical. Smaller, lighter gas molecules will leak through a hole much faster than larger, heavier ones.

Helium is often used as a "tracer gas" for high-sensitivity tests because its atoms are incredibly small and can find minuscule leak paths that air would not pass through as quickly. A leak rate specified for helium will be different than one specified for air for the exact same physical hole.

How Leak Rate Translates to Real-World Performance

The true purpose of measuring a leak rate is to predict how a product will behave in its intended environment. It’s a predictive quality control tool.

Predicting Water Ingress (IP Ratings)

A common application is certifying electronics for waterproof ratings like IP67 (immersion up to 1 meter for 30 minutes). It is slow, destructive, and impractical to test every single unit by submerging it in water.

Instead, manufacturers use a non-destructive "dry test." They determine the maximum allowable air leak rate that correlates to passing the IP67 water test. Every device on the assembly line is then quickly pressurized and checked against this air leak limit, ensuring no water will get in.

Ensuring Product Longevity and Safety

Leak rates are critical in many other industries:

- Medical Devices: A sterile implant or surgical tool must have an extremely low leak rate to prevent contamination by microorganisms.

- Automotive: Fuel system components, airbag inflators, and air conditioning systems are all tested to ensure they don't leak flammable fluids or refrigerants.

- Electronics: Sealed components are tested to prevent humidity and moisture from entering and causing corrosion or short circuits over the product's lifespan.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Pitfalls

Defining a leak rate is a balancing act between cost, manufacturing capability, and the product's performance requirements.

The Myth of the "Perfect Seal"

Achieving a true zero leak rate is physically close to impossible and economically impractical for most products. The goal is not perfection, but control.

The engineering team must define a leak rate that is low enough to guarantee the product functions safely and reliably for its expected life, but high enough that it can be consistently and affordably manufactured.

Confusing Leak Rate with Hole Size

A common mistake is to assume a certain leak rate equals a specific hole size. This is incorrect. A leak rate is a measure of flow, which is a function of both the hole size and the pressure.

A 1x10⁻³ mbar·L/s leak rate could be a tiny hole at high pressure or a slightly larger one at low pressure. The rate itself is the functional measure; hole size is just one contributing factor.

Your Test Method Determines Your Result

The method used to measure the leak rate—such as pressure decay, mass flow, or helium mass spectrometry—has a significant impact. Simpler methods like pressure decay are fast and cheap but less sensitive. Tracer gas methods are slower and more expensive but can detect far smaller leaks.

The chosen test method must be sensitive enough to reliably measure the target leak rate specification.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Setting a leak rate specification is about defining what "good enough" means for your specific application.

- If your primary focus is preventing water ingress (e.g., IP67): Your specification should be based on an established correlation between a specific air leak rate and passing the required water submersion test.

- If your primary focus is maintaining long-term vacuum or sterility: You need a very low leak rate (e.g., 1x10⁻⁶ mbar·L/s or lower), which almost always requires testing with a sensitive tracer gas like helium.

- If your primary focus is preventing dust or brief splashes: A more lenient leak rate is acceptable and can be verified with faster, less expensive air leak testing methods like pressure decay.

Ultimately, defining a leak rate transforms the abstract goal of "being sealed" into a measurable, achievable engineering target.

Summary Table:

| Key Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| Leak Rate (Tightness Rate) | A quantifiable measure of fluid escaping from a sealed object over time (e.g., mbar·L/s). |

| Standard Unit | Millibar-liters per second (mbar·L/s). |

| Primary Use | Predictive quality control to ensure products meet safety, reliability, and performance standards (e.g., IP ratings). |

| Common Test Gases | Air (for general use) or Helium (for high-sensitivity detection of minute leaks). |

Need to Define or Test a Leak Rate Specification for Your Product?

Understanding and accurately measuring leak rates is fundamental to ensuring the reliability and safety of your sealed components. Whether you're targeting a specific IP rating for waterproofing, ensuring long-term sterility for medical devices, or maintaining a vacuum, the right testing equipment is critical.

KINTEK specializes in precision lab equipment and consumables for laboratory needs, including advanced leak testing solutions. Our expertise can help you select the right method—from pressure decay for cost-effective checks to helium mass spectrometry for ultra-sensitive detection—to meet your exact specifications.

Let us help you transform the abstract goal of a 'perfect seal' into a measurable, achievable target.

Contact our experts today to discuss your application and ensure your products are built to last.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Filter Testing Machine FPV for Dispersion Properties of Polymers and Pigments

- Circulating Water Vacuum Pump for Laboratory and Industrial Use

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- Oil Free Diaphragm Vacuum Pump for Laboratory and Industrial Use

- KF/ISO/CF Ultra-High Vacuum Stainless Steel Flange Pipe/Straight Pipe/Tee/Cross

People Also Ask

- What is the water content of pyrolysis oil? A Key Factor in Bio-Oil Quality and Use

- Why are PTFE beakers required for hafnium metal ICP-OES validation? Ensure Pure Sample Dissolution

- How do you test the capacity of a lithium-ion battery? A Guide to Accurate Measurement

- Why is coating thickness important? Achieve Optimal Performance and Cost Control

- What are the advantages of using PTFE filters for ionic component analysis? Ensure Accurate Sample Quantification